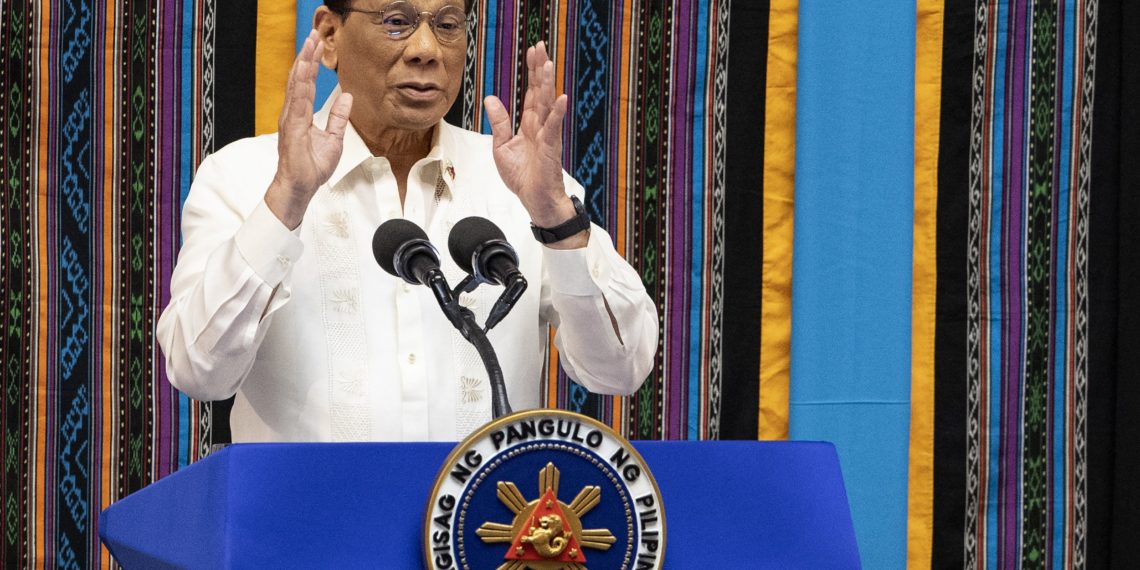

Earlier this week, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte delivered his fourth “State of the Nation” address, marking the first half of his 6-year presidency. The rambling speech, which lasted for more than one and a half hours, will likely reinforce people’s pre-existing attitudes about him. Critics will see the misogynistic jokes and defeatism towards China, while supporters will praise his signature candor, anti-corruption posture, and proposed policies like the restoration of the death penalty for plunderers and drug traffickers.

In his speech, Duterte himself saw his first three years as a success. He trumpeted the cleanup of Boracay Island and Manila Bay, the reduction of poverty “from 27.6 percent in the first half of 2015 to 21 percent in the first half of 2018,” the massive infrastructure projects under the government’s “Build, Build, Build Program” as well as the ratification of the Bangsamoro Organic Law which grants expanded autonomy to the Muslim-majority areas in Mindanao.

Although unspoken, the spectacle of the entire speech also spoke of Duterte’s political success – notwithstanding some major setbacks like failing to change the Constitution. The new House Speaker, Alan Cayetano, was installed largely through Duterte’s intervention while two of his closest aides since his long tenure as Davao mayor – Bong Go and Bato Dela Rosa – were in attendance as newly-elected senators. The latest surveys, moreover, show the president as being more popular than ever.

Doubtless, this sustained political momentum has empowered Duterte to declare that, far from being a lame duck, he will end his term “fighting.”

Duterte’s Popularity

Whether because or in spite of his administration, it must be acknowledged that the first three years of Duterte were good for many Filipinos. The economy has continued to grow. Remittances from overseas workers have continued to flow. The service sector, as well as various industries, continue to provide job opportunities, albeit mostly contractual. Thanks to the Salary Standardization Law signed by former President Benigno Aquino III, government workers earn more; thanks to the TRAIN Law signed by Duterte, they – alongside many other Filipinos – get taxed less.

The Bangsamoro Organic Law, meanwhile, represents hope in a region that has been mired in conflict for decades.

https://twitter.com/cnnphilippines/status/1070821536301408256

The president has signed other consequential laws. One of them, for example, guarantees free tuition in state universities and colleges, while another one guarantees health insurance coverage by virtue of citizenship. Policies like extending the validity of passports and driver’s licenses also took place during his term: simple but very meaningful for everyday Filipinos. Meanwhile, regardless of their merit, the infrastructure projects are a powerful visual projection of a government that is doing “something.”

All of the above explains, at least in part, Duterte’s continued popularity.

Poor Governance

Whatever Duterte’s successes have been, however, they are undermined by his overall governance – from his appointment of unqualified supporters and military men to various government posts (such as a retired army general to head the health insurance corporation) to his idiosyncratic, China-centric foreign policy and poor leadership that contributed to an insufferable months-long delay in passing the national budget. In terms of work ethic, Duterte has also been notorious for being absent or late in various events, and the State of the Nation address was no exception.

In his speech, he repeatedly claimed to be against corruption, but he has surrounded himself with individuals heavily linked to corruption, including Imelda Marcos, who remains at large despite having been convicted with graft and meted with a prison sentence. In what future generations will likely – hopefully – remember with infamy, Duterte allowed the burial of Imelda’s husband, the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos, in the national heroes’ cemetery.

The Duterte administration has also resorted to the persecution of its critics, including Senator Leila de Lima who is still in jail for vague drug-related charges, as well as the highly-regarded journalist Maria Ressa who is facing a host of charges. Days before the speech, known Duterte sycophants filed a baseless case of sedition against government critics including Vice President Leni Robredo and four Catholic bishops – in a sign that this trend is likely to continue.

War on Drugs

The war on drugs, as Senator de Lima noted in a The New York Times opinion piece, is a “pretense” to quash opposition through a number of means, including the release of “lists” that are supposed to contain politicians and personalities involved in drugs. Since Duterte took office, at least eleven mayors have been killed, one of them while singing the national anthem during a flag ceremony. Because these deaths are hardly, if ever, independently investigated, we may never know who ordered these assassinations. The only thing we can conclude is that the current environment of impunity has enabled them.

Beyond the human toll, the drug war has had other adverse consequences – from the pursuit of misguided, wasteful policies like mandatory random drug testing in schools to the construction of “mega-rehab facilities.” Moreover, Duterte’s approach to drugs seems to have influenced other countries in the region to follow suit.

To defend Duterte’s “drug war,” the Philippines has descended from being a beacon of democracy and human rights to a pariah of the international community, pulling out of the International Criminal Court and opposing a U.N. vote to condemn human rights violations in Myanmar. When an Iceland-led U.N. Human Rights Commission resolution called for an investigation of the Philippine situation, Duterte responded by saying: “What’s the problem of Iceland. It has only ice. That’s your problem, you have too much ice.”

Victims of Duterte’s Policies

The Philippines’ international reputation, indeed, is one of the victims of Duterte’s administration.

But the worst sufferers are the poor who bear the brunt of Duterte’s policies.

They include the fisherfolk, farmers, and other marginalized sectors who are likely to be affected by the provision of the tax reform law.

They include those at risk of displacement due to environmentally-impactful projects like the Kaliwa Dam and the Chico River Irrigation Pump (both of which, incidentally, are linked with questionable loans from China).

They include the indigenous peoples in Mindanao who are forcibly evacuated due to incessant militarization of their domains – the same peoples whose schools have recently been suspended ostensibly because they teach students to rebel against the government.

They also include the fisherfolk whose livelihood is compromised by the virtual Chinese occupation of their traditional fishing grounds – notwithstanding a U.N. ruling in favor of the Philippines. When a Filipino fishing boat got rammed and its 22 capsized men abandoned by a Chinese vessel last month, Duterte could only say: “I’m sorry, but that’s how it is.”

Last but not least, they also include those who are killed, orphaned, and widowed due to Duterte’s fake and hypocritical “drug war.” While both the drug-related killings and the violence against the poor are not unique to his presidency, the magnitude and scale have led scholars and activists alike to call the bloody anti-drug campaign a “genocide” and demand a U.N. investigation. The government insists that contrary to independent estimates that place the number of people killed at 27,000, the real number is only 5,526 – as if such number, or any other figure, is any less reprehensible.

“If you can provide me with a good comfortable cell, heated during wintertime, I want to go — and an air-conditioned during hot weather. And conjugal visits, unlimited, so we can understand each other,” Duterte jokingly said during his State of the Nation, off-script, about the possibility of being convicted by the International Criminal Court. It has become a recurring theme in his talks.

His premonitions may yet come true, and Filipinos may begin to look to other leaders for hope, but for the victims of the violent policies he has enabled, justice can’t come soon enough.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.