With more than 25 million people forcibly displaced from their countries by the end of 2018, the world currently faces an unprecedented refugee crisis. Among the countries with the highest rates of displacement are Syria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Afghanistan – all of which are riven by war and instability.

Also on this list, however, is Eritrea. In contrast, the small East African nation has been mostly at peace since it won its independence struggle against neighboring Ethiopia in the early 1990s.

To Martin Plaut, a senior researcher at London’s Institute of Commonwealth Studies, these figures are illustrative of the despair and hopelessness faced by those who live under what he calls the “most secretive, repressive state in Africa.”

Unlike other, more famous authoritarian and totalitarian states around the world, Plaut notes that the Eritrean regime makes no pretense of even having a constitution, a representative legislature, elections, or a semblance of a free press.

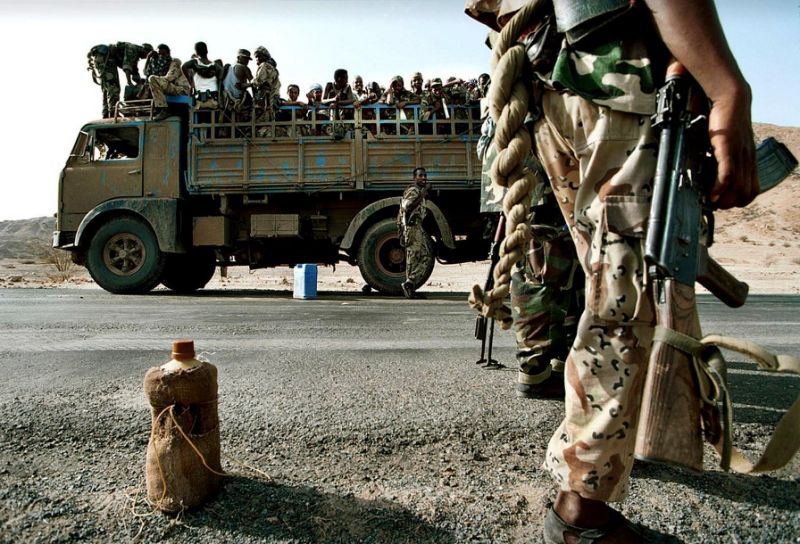

The fate of its citizens are dictated by the whims of the regime – headed by independence leader turned dictator Isais Afwerki. All Eritreans are subject to conscription into the military and can be compelled into forced labor that the U.N. says “effectively abuses, exploits and enslaves them for years.”

Those who step out of line can be detained indefinitely under shocking conditions. Others are killed. There are no courts to hear their appeals.

Plaut, the former Africa Editor of the BBC’s World Service, set out to tell the “untold story of how this tiny nation became a world pariah,” publishing “Understanding Eritrea: Inside Africa’s Most Repressive State,” in 2016. With the release of an updated version of the book this year, The Globe Post spoke to Plaut to shed light on the widespread abuses in Eritrea that have gone largely unnoticed by the outside world.

The Globe Post: After a thirty-year struggle, Eritrea won its independence from Ethiopia in 1993. If you can take us back, what went wrong in the immediate wake of independence and how did the government that’s ruled since come to power?

Plaut: Actually, in effect, it started before that in 1991 when they actually took the capital. What they rightly did was to say, “we won’t formally declare independence until there’s been a U.N. supervised referendum.” And the reason for that was that nobody would ever be able to turn round and say, well, “you just took it by force. It can be taken back by force. The people never really supported you.” So, although they actually declared it formally in ‘93, they really held it from ‘91.

In the beginning, things were fine. But gradually it became clear to President Isaias [Afwerki], who led the independence struggle for 30 years, that things were not going the way he expected them to. A lot of the troops that he had under his command, all of whom were volunteers, all of whom were guerrilla fighters, had been fighting, some of them, for 10, 15 years without pay.

They were only used to getting effectively pocket money and food. lodging and, of course, ammunition and weapons. And they began to turn round and say, “well, hang on, we now have to look after our families. They’re in deep need. We need a bit of money.” There were also concerns about the way the veterans who had been injured – some of whom had lost legs, arms, some of them very badly crippled – how they were being treated.

Both these groups began to express concerns, and Isaias was just outraged that anybody would turn around and question his authority. He had ruled for 30 years with an absolute iron rod. And it was needed because they were up against an enemy that was 10 times its size in terms of population.

Ethiopia was also receiving arms – first from the United States and then from the Soviet Union – in vast quantities. So in order to win against them, you had to be completely and utterly ruthlessly disciplined. Some things happened during the liberation struggle that were pretty, shall we say, unattractive, even against their own people. Some people were shot for indiscipline, that kind of thing, and for questioning his authority.

But when he discovers that his authority is being questioned after independence, he begins reacting in the same way. There was a famous incident where some of the disabled tried to walk into town to complain to him, and they were met by the police and the army who opened fire on them. To open fire on your own disabled is pretty appalling.

TGP: You say that Eritrea is the “The most secretive, repressive state in Africa.” What sets the Eritrean government apart in your mind from other repressive, authoritarian ones on the continent and what are some specific practices or policies that you find to be particularly egregious?

Plaut: Most other governments at least make a pretense of having a constitution and having a parliament, even if it’s manipulated, and allowing a semblance of a free press. You take a pretty authoritarian regime which doesn’t hesitate to repress and kill its opponents and its journalists, like Rwanda. But they do have a constitution. They have a parliament which meets and the parties function. They might be all be controlled by [President Paul] Kagame, but there is a semblance of some political space.

None of these apply in somewhere like Eritrea. There is no constitution that’s been ratified. The parliament has been prorogued. It hasn’t met for years now. Even the ruling party hasn’t had a Congress for many, many years. There are no other parties that are allowed to operate in Eritrea. There is no independent media. Even organizations like Al Jazeera, BBC, Reuters are not allowed to have journalists permanently stationed there.

So, that’s really what singles it out from other repressive regimes in Africa, some of which are extremely bad and very repressive. But they do have some semblance of legitimacy and that is something President Isias has no time for.

TGP: The 2018 UN refugee assessment report notes that Eritrea is among several countries with the highest rate of displacement in the world. Others mentioned in the same category include Syria and the DRC, both of which are the sites of wars and major instability. What does it say about Eritrea that so many people are fleeing the country despite the fact that there is no conflict there?

Plaut: I think you’re absolutely right to single that out as a clear indication of what is wrong and why it is so peculiar. The reason is simple. The system of compulsory conscription, which effectively operated during the war of liberation, was extended after under the guise of a national service and today is indefinite. Some people have been in national conscription for over 20 years. They’re hardly paid at all. They can be deployed to the most remote corners of the country and they have no ability to lead an independent life and live under military discipline.

Some of them think, “well, this is it. My whole life could be spent, stuck in a trench in the most remote corner of the country,” supposedly guarding it against the Ethiopians who might or might not attack or against Djibouti, with whom they also have a quarrel. This just fills people with such dread and despair that although there’s an extremely high penalty for desertion, you will be shot, they decide to cross. When the border was opened briefly with Ethiopia after the peace agreement last year, up to 500 people were leaving each day. And this is a small population. There are various estimates, but the government figure is 3.6 million people. To have 500 leaving a day, you’re in a shrinking situation.

TGP: I wanted to ask you a bit more about the practice of conscription into permanent military service. As the United Nations reported: “Thousands of conscripts are subjected to forced labor that effectively abuses, exploits and enslaves them for years.” Just how widespread is the practice and what kinds of specific labor are people forced into?

Plaut: Well, you have to spend your last year of schooling at the military academy at Sawa, which is in the west of Eritrea and a pretty remote area. If you’re lucky and have the right connections, after your basic training of about 18 months, you might then get a job perhaps in the civil service or be sent to work for a general.

But you are entirely at the whim of your senior commander. Women complain of being abused sexually, of being forced to perform domestic chores for officers. Men are sometimes being sent to the mines in some of the toughest conditions you can possibly imagine. The Eritrean coast gets up to 50 degrees centigrade (122 degrees Fahrenheit), some of the hottest conditions in the world. To be mining or building roads under those conditions is extraordinarily tough.

You are at the whim of the regime who, if you step out of line, can lock you up indefinitely. There are no courts to whom you can appeal. Somebody was released recently who had been kept for five years in a shipping container and let out about once every week or two weeks. They were almost blind. There was no light. Those are the kinds of circumstances in which people can be detained. People are just in despair.

TGP: Interestingly, you note that the government has played a role in supporting the Saudi-coalition waging a brutal war against the Houthis in Yemen. Why has Eritrea become involved in that war and how can we understand the regime’s foreign policy towards the region more broadly?

Plaut: Some years ago, the government was in alliance Iran, which of course is on the other side of the war in Yemen. But quite frankly, I think they were wooed by the Saudis and the United Arab Emirates, who, as you say, are fighting Houthis and fighting the Iranians. Frankly, I think it was a question of money. They were given really substantial sums of money. None of this is ever revealed. No budget is ever published in Eritrea. So there’s no way of knowing. But that is the most likely explanation.

They simply swapped sides as a result. The Saudis and the UAE can use Eritrea’s ports and airfields and they use them to attack the Houthis. There are also reports of some Eritrean troops manning some of the islands between Yemen and Eritrea in the Red Sea. And they are also part of that defense operations to prevent the Iranians from bringing assistance to the Houthis. This has all been shown by satellite imagery and there’s no doubt about this.

More broadly, the Eritreans have managed to fall out and then mend fences with every single one of their neighbors at various times. They’ve had a border war with Ethiopia. They’ve had a clash along the border with Djibouti. The border with Sudan was closed until earlier this year because relations were so bad.

They’ve literally fallen out with almost everybody because everything is run at the whim of President Isais. And he actually thrives on stirring up trouble and difficulties for his neighbors. He’s a past master at mobilizing and manipulating events in neighboring countries. And that’s the way that he operates.

TGP: The human rights abuses and repressive policies of governments like those in Saudi Arabia, for example, or North Korea are quite infamous and well known to Western audiences. But it seems to me that many in the West have probably never even hear of Eritrea. Why do you think that is?

Plaut: Well, you mustn’t forget that it doesn’t have any strategic reserves of oil or another mineral that is absolutely vital. They are on an important sea route on the Red Sea, but that’s about their only claim to fame. They’re quite a large country, I suppose, in European terms. But they’re not a large country in terms of Africa. And they, therefore, haven’t really caught the attention of the world.

Anything that has increased their importance, certainly in the American sense, is that there have been suggestions that the Russians might get a naval base in Eritrea, but those have not been confirmed. There is something of a sort of naval arms race in the Red Sea because you have both the United States and the Chinese operating out of Djibouti. And they sort of have an uneasy relationship with each other because of the close proximity of their bases.

So it is possible that there might be more strategic interest in Eritrea because of this and because of their involvement in the war in Yemen. Apart from that, they have one other mineral which has been recently discovered, a vast potash deposit, which straddles the border with Ethiopia. That is one mineral that really does look interesting to the outside world. It is an extraordinarily rich deposit. But apart from that, there’s no particular reason for anybody to have taken notice of the country.

More on the Subject