Amid the destruction and deluge of the war in Syria, a remarkable experiment in grassroots democracy has taken root across a large swath of the country’s Northeast. This experiment is now under grave threat of being destroyed, as Turkey and its proxy forces lay siege to the area and Syrian regime forces have begun to return to the region.

The “Rojava Revolution” began, roughly, in 2012, when President Bashar al-Assad withdrew his forces from Northern Syria as the war escalated in other parts of the country. In the absence of the regime, the people of the predominantly Kurdish region of Rojava declared their autonomy and produced a new constitution in early 2014, titled the “Charter of the Social Contract.”

The core principles outlined in the social contract are decentralized democracy, feminism, secularism, ecology, and ethnic pluralism.

In it, the people of Rojava – a territory of roughly four million people spanning nearly a third of Syria – declare their aspirations to build a society “free from authoritarianism, militarism, centralism and the intervention of religious authority in public affairs.”

The charter declares men and women equal under the law and “mandates public institutions to work towards the elimination of gender discrimination.” All elected bodies must be made up of at least 40 percent women and a woman must co-chair all public institutions.

The document ratifies the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and guarantees free expression. Public education, health care, and decent work are guaranteed as rights. It is fundamentally anti-capitalist, promoting a communal-based economic system aimed at “guaranteeing the daily needs of people … to ensure a dignified life.”

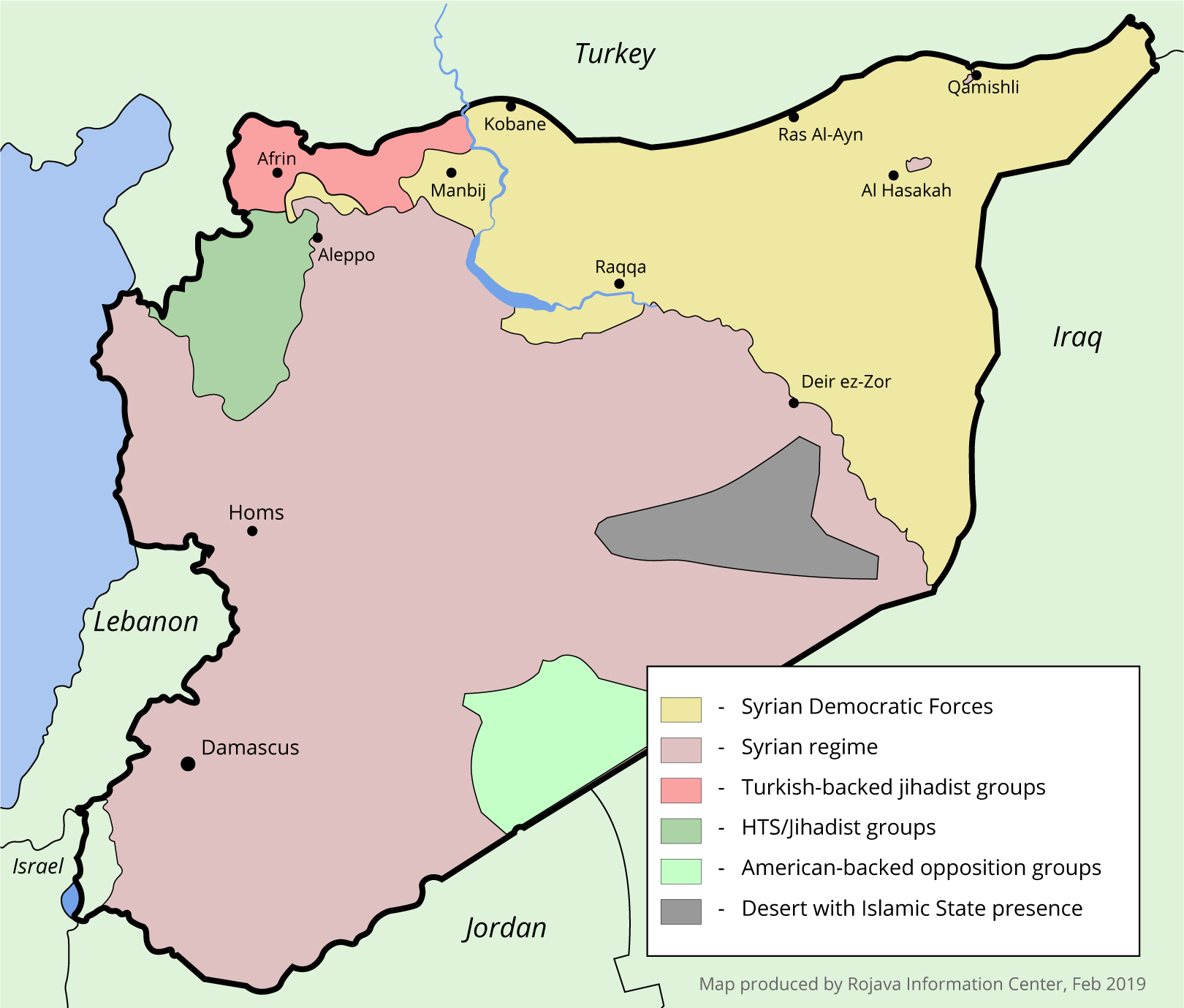

Abolishing or minimizing hierarchy is a central tenet of the Rojava Revolution. Under the social contract, the regional government is administered through three “Cantons” – Afrin, Kobane, and Jazirah – under which decision making is as localized as possible, all the way down to the neighborhood or “commune” level.

Roots of the Revolution

How these ideas came to take hold in this enclave in the heart of the Middle East is a strange and improbable story in itself. The ideology at the foundation of the social contract can be traced back to the radical leftist circles of New York’s Lower East Side in the 1960s and ’70s and the work of one man, Murray Bookchin.

Bookchin, a self-educated historian and political philosopher, devoted decades of his life writing about libertarian socialism and anarchism before his death in 2006. A Marxist in his youth, he became disillusioned with communism after the rise of Joseph Stalin and came to champion a decentralized model of socialism very different from the state-dominated system of the Soviet Union.

Emphasizing the role of hierarchy in society, Bookchin became a prominent figure in anarchist circles, though he later rejected the term, embracing “social ecology” and “communalism” instead.

Two years before his death, Bookchin received an unexpected letter from an intermediary of Abdullah Öcalan, the imprisoned leader of Turkey’s Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

Beginning in 1978, Öcalan and the PKK began waging a separatist insurgency in Turkey, where Kurds have long been oppressed. The ultimate goal was to create a united Kurdistan under a Marxist-Leninist government that would span across the Kurdish regions of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran.

Öcalan was captured In 1999 and sentenced to life in prison on a remote Turkish island. By chance, he came across one of Bookchin’s books and underwent a political conversion while in prison, abandoning communism and embracing Bookchin’s decentralized model of socialism.

From solitary confinement, Öcalan penned a manifesto in 2011 called “Democratic Confederalism” based largely on the work of Bookchin. Even from prison, the guerilla leader’s ideas continue to hold a considerable degree of sway among the ranks of the PKK, which have almost entirely followed his lead in rejecting communism in favor of the Bookchin model.

Öcalan’s ideas also trickled over the border into Northern Syria, where he is a revered figure among Syrian Kurds.

In an interview with The Globe Post, Bassam Saker, the U.S. Representative for the regional political body – the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC) – conceded that there is widespread “sympathy” for Öcalan in Rojava, but stressed that the Syrian Kurds and their fighting force – the People’s Protection Units (YPG) – are not directly associated with the PKK.

The PKK is considered a terrorist organization by Turkey, the United States, and the European Union, and leaders in Rojava have gone to lengths to distance themselves from the organization. The third paragraph of the social contract clarifies that “the Charter recognizes Syria’s territorial integrity,” drawing a distinction between Öcalan’s separatist movement.

“We want Syria united. We never want to be separated,” Saker said.

An Imperfect Effort

These assurances have not swayed Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who considers the YPG and PKK to be one and the same. But they were good enough for the United States, who partnered with the YPG and allied Arab militias under the umbrella of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in their mutual campaign to destroy ISIS.

While the men and women of the YPG fought a valiant and bloody ground war against the so-called Caliphate, the people of Rojava endeavored, imperfectly, to implement Öcalan’s vision at home.

Despite the idealism of the social contract, Rojava is not a utopia.

Though ethnic inclusivity is celebrated in the constitution, Amnesty International reported in 2015 that YPG soldiers forcibly removed Arab families from several villages captured from ISIS. These reports have been disputed by regional officials.

And while environmental sustainability is cited as a leading principle in the social contract, journalists who have visited the region have documented significant, widespread pollution.

“Hitching rides around Rojava, I was appalled by the environmental degradation. The most educated people throw their garbage directly out the window, and flattened trash accumulates like leaf litter in the forest,” Seth Harp wrote in his famous 2017 Rolling Stone magazine article, “The Anarchists vs. the Islamic State.”

Saker acknowledged that environmental initiatives have been difficult to implement but insisted that the sentiment is sincere and that conditions could be improved in the future.

There are also external factors beyond Rojavan control that are making life difficult for people there. The region’s borders with Iraq and Turkey are largely sealed, preventing imports of food and other goods. The Turkish government has intentionally created a water shortage, building dams to block the flow of rivers into the area. Aerial bombardment from the war has caused major infrastructure damage.

‘One Class’

But there have been major gains in implementing the ideals of the social contract as well.

The SDC is led by a woman, Ilham Ahmed, and women are represented in leadership roles in public institutions across the region. The YPG has an all-female fighting brigade, the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ), and command decisions are made jointly between men and women.

There is little hierarchy in the YPG. Generals are directly elected and are expected to wash their own clothes and perform chores like cooking.

“There were no ranks. You could go to your general, slap him behind his head and ask him for a cigarette. It was amazing,” an Italian who was one of about 75 foreigners to fight with the YPG against ISIS told Harp.

The principle of communalism has also manifested itself across the region. People work collectively to produce goods and services and are happy to share with anyone in need.

“If I ever so much as took a dollar bill from my wallet the Kurds would ward it off like a talisman of evil,” Harp wrote. “I saw no rich people, no corporations, no banks, no big houses, no fancy cars, no one homeless or begging or starving. The people were of one class and improbably cheerful.”

An American man who volunteered to fight with the YPG and spoke with The Globe Post on the condition of anonymity was adamant that the Rojava Revolution is much more than nice words on paper.

“The thing that impressed me most was how incredibly kind and loving the people are. It might be a bit cliche to say but they would give you the shirts off of their backs,” he said.

“Even after all the oppression, injustice and torture they have endured, the people of Rojava have the biggest hearts of anyone I know.”

A City on a Hill?

In addition to overhauling the region’s political and economic systems, the people of Rojava have also implemented an alternative justice system aimed at promoting “social peace” instead of punishment.

On a visit to the region in 2015, Carne Ross, a former British diplomat and documentary filmmaker, witnessed the system in action. After a murder in Jazira, the families of the victim and the perpetrator got together for a formal lunch. After a process of “compensation, apology and forgiveness,” the victim’s family accepted the perpetrator’s apology and he was released from prison.

“I was staggered and moved,” Ross wrote in an article for the Financial Times. “I thought of the barbarity of Rikers Island prison … No one in [the U.S.] would claim that a system premised on punishment over reconciliation has achieved ‘social peace.’”

The death penalty has also been abolished, even for ISIS detainees, according to Saker.

And despite reports of abuses of Arabs by the YPG, there has been real progress made in creating an ethnically pluralistic society.

Arabs, Assyrians, and other ethnic minorities participate in public institutions, including the SDC and the SDF.

“The majority of the SDC – and even the SDF – are not Kurdish. But there is a social contract and they believe in that,” Sakar said.

After originally renaming the territory the “Democratic Federation of Rojava – Northern Syria,” representatives voted in 2016 to drop “Rojava” – a Kurmanji word meaning “the west,” referring to Western Kurdistan – from the official title in the name of ethnic inclusivity. The region is now commonly referred to as the “Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria” or the “Self Administration.”

Saker himself is an Arab from a different region of Syria. Following the outbreak of demonstrations against Assad, he became a leader in the opposition and visited Rojava for the first time in 2015. He was “amazed” by what he saw and quickly accepted an invitation to join the SDC.

Saker believes deeply that if the region is allowed to continue its autonomy in peace, the Rojava project could be a model for the whole of Syria, and even the entire world.

‘Ethnic Cleansing’

But all of this now in serious jeopardy of being destroyed.

On October 9, Erdogan launched “Operation Peace Spring,” a major offensive against the YPG with the stated intention of driving the Kurds out of the border region and resettling millions of Arab Syrian refugees there.

The Turkish president has already successfully destroyed the project in Afrin – one of the original Cantons established in the social contract. In March 2018, he launched an offensive there, driving out the Kurdish population and bringing the area under the control of radical, Islamist militants.

“Afrin, it was secular. The people, everyone lived together. The woman like a man. It was stable,” Saker said. “Now … there is an ethnic cleansing for the Kurdish. No Kurdish anymore there. If someone Kurdish stayed there – the [elderly] – they are in a very bad situation.”

The situation for Rojava and its political experiment is now extremely dire as Erdogan vows to extend the fate of Afrin to the rest of the region, a prospect Saker said is “unacceptable.”

On Tuesday, Russia and Turkey reached an agreement to jointly patrol the border area and enforce Erdogan’s demands that the YPG withdraw from the region. The deal has shattered hopes that the SDC could negotiate with Moscow and the Syrian regime to pressure Turkey to abandon the operation and preserve a semblance of autonomy for Rojava.

“Almost everyone I have ever loved and cared about is in danger of genocide because the world is sitting around and doing nothing,” the former American YPG fighter said. “I feel like I am watching my home being destroyed in front of me and there is nothing I can do about it.”

The latest Turkish offensive was made possible by U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw a small number of American forces from the region who were stationed with the SDF, serving effectively as a deterrent.

Slamming Trump’s decision, Congressman Ro Khanna described Rojava as a “society full of dance and color and music and vitality.”

“There’s a lot of women leadership and feminist values and a very vibrant civil society and culture,” he told The Globe Post on Monday. “They haven’t been able to establish this anywhere else. They finally established this and now that’s being destroyed.”

Though Turkey agreed to extend a tenuous ceasefire negotiated with the U.S. on Tuesday, Erdogan remains committed to preventing an autonomous, predominantly Kurdish region from existing near the Turkish border and has given the YPG an ultimatum to withdraw from a 32 kilometer deep “safe zone” along the border or be slaughtered.

In the face of the Turkish invasion, the people of Rojava have found themselves with few friends by their side. While Trump has threatened to “destroy” the Turkish economy if Erdogan crosses an undefined “line,” he’s also largely appeased Turkey and has criticized the Kurds, calling them “communists” and repeatedly saying they’re “not angels.”

“I’m afraid because I feel that nobody wants us to have our model,” Saker said.

“We are alone … but we will never give up on this idea.”