Far-right forces have been ascendant around the globe in recent years, leading some to seriously question the strength of liberal democracy for the first time in decades.

What is causing this resurgence continues to be a matter of contention.

Do people who vote for far-right candidates do so because they support their agenda, or is it better to understand their vote as a protest against the hated elites who dominate the political establishment?

Is economic anxiety driving support for the far-right, or is it racism, xenophobia, and cultural resentment?

Has the media played an unwitting role in fueling the far-right’s narratives?

Has neoliberalism and the extreme wealth inequality it’s caused created the conditions to make the far-right’s rise possible?

Cas Mudde, a professor in Politics at the University of Georgia, has been studying the far-right for decades and is one of the world’s foremost experts on political extremism. As he puts it in his Twitter bio, “Used to study fringe politics. Now study mainstream politics.”

With the recent release of his latest book, “The Far Right Today,” The Globe Post’s Bryan Bowman spoke with Mudde about the forces driving the success of the global far-right, and how these forces might best be challenged.

The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Bowman: At the outset of your book, you note that the far-right is in power in three of the five most populous countries in the world – Brazil, India, and the United States. What is the common thread that ties these different governments together under the umbrella of the far-right? When we talk about the far-right, what specifically are we talking about?

Mudde: I think what these three have in common is a combination of nativism, authoritarianism, and populism.

So nativism being a xenophobic form of nationalism. Authoritarianism being seeing pretty much everything as a law and order issue. And populism – the belief that the elite is corrupt and that these leaders are the voice of the people.

Bowman: Is that the same criteria you use for other governments or other parties around the world that are also generally referred to as being far-right?

Mudde: Well, the far-right itself includes both the radical right and the extreme right. And the difference is that the extreme right is against democracy as such. And you can think about them, most notably, as fascists. Whereas the radical right does believe in elections, but has issues with aspects of liberal democracy, most notably minority rights, rule of law, separation of powers.

Now, almost all of the more successful far-right parties are of the radical right. However, there are some extreme right parties that have success as well, most notably Kotleba (Our Slovakia Party), (Greece’s) Golden Dawn for a while. And you see that some radical right figures like (Brazil’s) Jair Bolsonaro are actually flirting with extreme right kind of measures in the way he flirts with military dictatorship.

Bowman: As for the causes that are driving the success of the far-right around the world, you identified a number of key ongoing debates, the first of which is this debate about protest versus support. So is it better to see support for the far-right electorally as genuine support for their ideology or as a protest against the political establishment? How do you approach that question?

Mudde: I think that both the question of protest versus support as well as economic anxiety versus cultural backlash – it is a combination of the two in both cases.

Of course, if you are supportive of a radical right agenda, then you protest against liberal democrats because they have opposing views. But it is clear that it is not a random protest. What we find in almost every country is that a majority of the often voters of far-right parties believe that they are far too many immigrants in the country, that they are a problem.

So they clearly agree with some of the key aspects of these parties’ agenda, but they also clearly indicate that they dislike all the other parties. So they both protest and support.

Bowman: On the economic anxiety versus cultural backlash or racism debate, that one has been particularly potent in the United States. You note that there have been some studies and some data that suggest that the cultural or racial part was stronger than the economic anxiety part in terms of Trump’s election. But acknowledging that, you don’t think that they’re necessarily mutually exclusive either, right?

Mudde: No. I think that for part of the electorate of the far-right, economic anxiety plays a role. However, it is translated through social or cultural fears.

It’s not just that they have anxiety about their own economic situation. They also believe that the reason for that economic problem are immigrants rather than neoliberalism.

So economic anxiety is part of it, but it’s not the main driver. And the other thing that we know is that there’s a whole lot of people – the majority of far-right voters – who don’t have economic anxiety. They’re not unemployed, they’re not poor. But they often do think that the economic situation of the country is bad.

That, again, can partly be explained by the fact that they are nativists and they think that the country is being swamped by immigrants. And because they think immigrants are bad, they believe that this is bad for the economy.

Bowman: You note in the book as well that neoliberal globalization is at the root of both of these theories. So for those who maybe aren’t familiar with the terminology, what is neoliberalism and what role or what is its relation to the far-right?

Well, in the most simplistic terms, it is by and large a belief in the market and that the market mechanism should be dominant, not just in the economy, but pretty much how to run the state. And as a consequence, there’s a kind of a world economy being created in which governments play a minor role.

Now, there are various aspects of that. One of the aspects of a neoliberal world market is immigration, because immigration is perceived to be part of that market and should not be regulated.

Another part is that job protection is undermined because the market will decide what the best conditions are and what the best wage is for something. All of these things – as well as the move of traditional industrial jobs away from the west to the developing world – all of these have profound effects on societies, particularly in the Western world, which means that by and large there are fewer old school blue-collar work jobs.

Bowman: What is the history of neoliberalism? How did it become the prevailing ideology or political framework?

Mudde: To a large extent neoliberalism has been around for a very long time and has been adjusted at times. But roughly in the 1980s, neoliberalism became pushed by right-wing parties, and in the early 1990s, the Social Democrats by and large adopted much of that agenda as well.

As a consequence of that political convergence, one of the things that happened was a privatization of a lot of the economy. Another one was that a lot of policy was now no longer made by politicians, but by kind of independent, expert organizations and therefore by economists. And politics as such became reduced.

Much of the industries that used to be controlled by the state, like public transport or telecommunication, were now part of the market and therefore also outside of the purview of the state.

Bowman: Interestingly, you also argue that major media has been a factor in the rise of the far-right, or at least played some role. You give the example of the so-called refugee “crisis” and how you feel the framing of that phenomena has been problematic. But you also say media has at times challenged the far-right. So what has been the media role as you see it?

Mudde: In most cases, the media are both a friend and foe of the far-right. They’re a friend in the sense that they largely push a similar agenda because of the privatization of most media, they’re now all pretty much driven by a profit motive. That means that they focus on issues that sell – crime, corruption, immigration – these issues are pushed disproportionately by the media.

However, there are very few media organizations that actually support the far-right. So what you have is, on the one hand, a media that sets the agenda and decides which types of issues and frames are being discussed, which are very much in line with the far-right but at the same time, will often say that the far-right itself is problematic.

So this is not a story of the media being big supporters of the far-right. Actually, overall, the media cover far-right parties and politicians pretty negatively. But they also cover them as well as their issues disproportionately.

Bowman: In recent years, we’ve seen a string of shocking terrorist attacks committed by individuals with far-right ideologies, from Charlottesville to Pittsburgh to Texas to Christchurch. Having studied these forces for a long time, do you feel that the terrorist threat from far-right extremists has been taken seriously enough? And how do you think officials can best respond to it now?

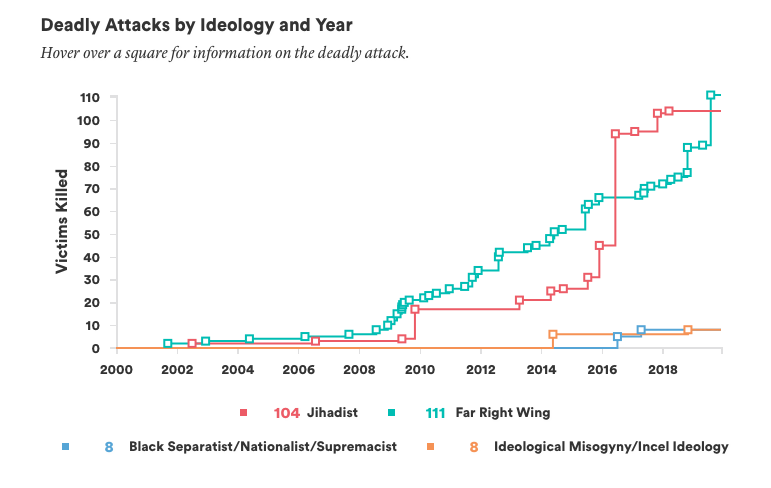

Mudde: Well, if you take a longer perspective, then probably far-right terrorism is not at a higher level than it used to be. It was higher in the 70s and 80s. At the same time, there has been a spike over the last few years.

What I think is particularly relevant is that in many countries, far-right terrorism was taken very seriously in the 1980s and 1990s, perhaps even too serious in the sense that the threat was exaggerated in countries like the Netherlands and to a certain extent Germany.

But after 9/11, almost all of the focus and the resources of counter-terrorism went to so-called Jihadist terrorism, which by and large just left services that monitored far-right violence completely understaffed.

And I think that is something that is finally being recognized. Over the last couple of years, we have seen, in various countries, intelligence services as well as politicians finally taking the threat of far-right violence seriously again.

In many countries, political violence that comes from the far-right is a much more serious threat than from any other sources, be they far left or Jihadist. That is now slowly getting accepted and recognized. But the resources are still lacking compared to particularly to Jihadist terrorism.

Bowman: Lastly, you write that there’s no simple answer to the question of how the far-right can be defeated. That there’s no “silver bullet.” But because you identified neoliberalism as being at the root of a lot of these issues, do you think creating alternatives to it that would be an effective way to counter far-right’s influence and appeal?

Mudde: Well, I’m a lefty, so I’m very happy to abandon neoliberalism. But I think it’s shortsighted to think that that will take care of the far-right because many of our societies are now multicultural. So irrespective of whether you abandon neoliberalism or not, that is an issue to be addressed.

I believe that particularly jobs should be protected better and to a certain extent there should be a more open and insightful conversation about how to regulate immigration and asylum seekers – not necessarily in the sense that there should be fewer – but that it should be clear that the state regulates it, which is not always the case very well in many European countries.

In the end, this is about how we view our society and how we view our nation. And as long as by and large, the assumption is still essentialist, where the Netherlands is seen as a country of Dutch people and Dutch people are kind of implicitly white and either Christian or secular, there is a sizable portion of the population that is not included and therefore by definition seen as foreign, alien, as not really part of us.

Whether we have neoliberalism or not, we’ll have to redefine who we are and be clearer about a lot of the implicit assumptions that we have had about how we see our society in terms of ethnicity, religion, and other things.

More on the Subject

Psychological Wage: Understanding Trump’s Support in Rural America