Internet blackouts restricted Iranians over the weekend as anger mounts over an accidentally brought down airliner. Authorities denied a “cover-up” on Monday after taking days to reveal the plane was accidentally shot down last week. The disaster has sparked fresh protests, while Donald Trump demanded that the Iranian government abstains from shutting down the internet.

However, data from Oracle Internet Intelligence Map, which tracks web connections, showed cuts to Iran’s international internet access on Saturday and Sunday. And on Monday, internet monitor NetBlocks reported a drop in connectivity at Tehran’s Sharif University ahead of any new demonstrations.

Confirmed: Drop in internet connectivity registered at #Sharif University, Tehran from 11:50 UTC where students are protesting for colleagues and alumni killed on flight #PS752; national connectivity remains stable despite sporadic disruptions on third day of #Iran protests

pic.twitter.com/LjaNNd4Ut2

— NetBlocks (@netblocks) January 13, 2020

The internet has been a serious weapon in the Islamic Republic regime’s inventory and was also utilized when street protests washed over the country this past November. Authorities cut off all online access for four days. Later, in December, internet services were disrupted again ahead of more planned anti-government demonstrations.

Iran’s Uprising

On November 15, millions of Iranians took to the streets to protest against their government following the announcement of sharp price increases. To halt the spread of anti-government sentiment, Tehran immediately cut off internet access throughout the country. But the strategy failed, as did the direct repression of protesters, many of whom remain active to this day despite an estimated 1,500 deaths and 12,000 arrests.

With the prior month’s protest movement stretching toward the end of December, the Iranian regime found itself short on ideas and decided to restrict internet access again.

NetBlocks confirmed that a widespread internet blackout went into effect on the morning of December 25, just as the nation was planning to commemorate those who had been killed in the first days of the uprising.

The government of Iran must allow human rights groups to monitor and report facts from the ground on the ongoing protests by the Iranian people. There can not be another massacre of peaceful protesters, nor an internet shutdown. The world is watching.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 11, 2020

The internet blackouts of November and December were far more extensive than anything the regime had attempted during riots in 2009 and 2017.

There are enormous economic, political, and social costs to cutting off the internet. But in this past year, unlike any other, the regime was willing to incur those costs in exchange for the vague prospect of impeding a nationwide revolt.

Tehran’s pursuit of this tradeoff should leave the international community with little doubt that Iran’s regime is lying when it expresses its ability to overcome domestic resistance.

High Economic Costs

The state-run news outlet Entekhab outlined the costs of cutting off the internet in a report published on November 21. Notably, it pointed out that a protracted commitment to such measures would quickly override the benefits the regime expected to gain by increasing gas prices.

According to the report, Iran’s economy lost about $1.5 billion within the four days of the November cutoff. This shows that the regime was well aware of the blackout’s consequences. Yet the suspension was kept in place for two further days in December because permitting free communication could have led to even worse ramifications for the Islamic regime. That is to say; it might have led to the Iranian people’s triumph over the theocratic system.

The regime makes little secret of the fact that freedom of speech is a threat to its hold on power. Speaking to ISNA News Agency in November, one officer of the hardline Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps said that sophisticated activist networks had developed before the uprising and that the disruption had gone a long way toward preventing them from capitalizing on the price hikes in a way that would destroy the establishment.

Speaking to the same news outlet three days earlier, Communications Minister Mohammad Azari-Jahromi similarly praised the blackout’s effects. “Certainly, this disruption of services has been a major blow to both the people and the businesses,” he said, “but maintaining the security of the country is very important.”

Less Information Leads to More Scrutiny

The economic cost of shutting down the internet is easily matched by the political cost.

Despite the domestic population being cut off from information, such measures actually bring more international scrutiny. According to the U.S. State Department, once Iran’s internet access was restored, 20,000 people reached out within days with documentary evidence of Tehran’s brutal repression.

President Trump brought additional attention to the shutdown, tweeting, “The Iranian government has become so fissiparous that it has shut down the whole internet system so that the great people of Iran cannot speak about the severe brutality that is going on inside that country.”

Long-Term Consequences

The resumption of internet blockages in December has many Iranians fearing that a permanent internet blackout is looming. Indeed, many Iranian officials have been promoting the concept of a “national information network” or “halalnet” that would effectively isolate Iran from the global internet and only allow for the exchange of regime-approved content.

Such a system would continually remind the international community of Tehran’s vulnerability and its desperate need to keep a tight grip on all public communication. But this message would be all the clearer to the Iranian people. And while it may inspire some to persist in their activism for the sake of exploiting that vulnerability, others will conclude that their homeland is a place in which it is impossible to make a life for oneself.

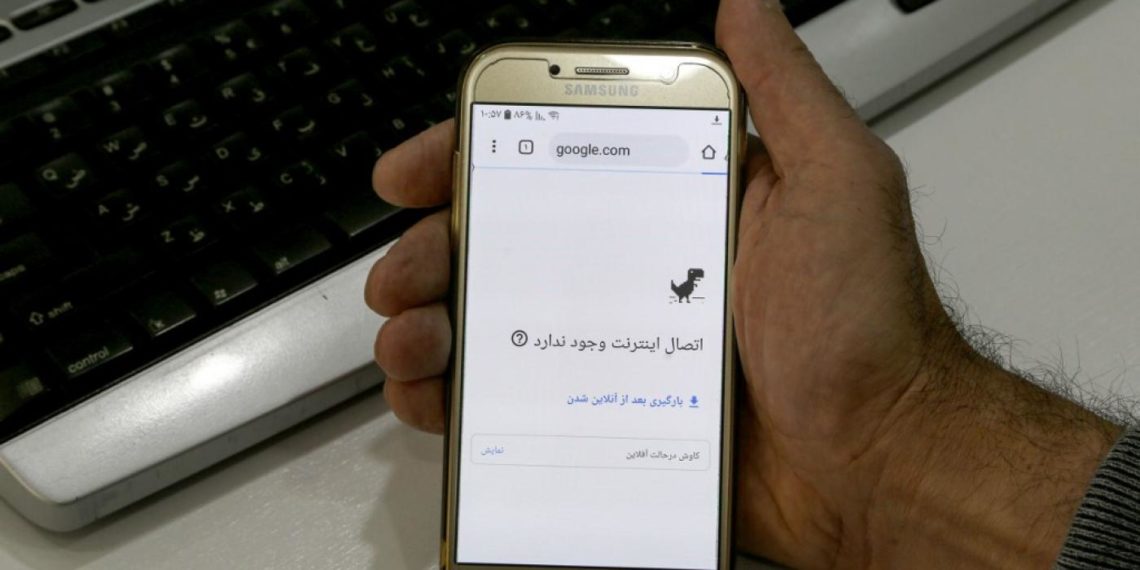

In some parts of Tehran there is no mobile data. pic.twitter.com/g6c5wiumS9

— AmiR Rashidi (@Ammir) January 13, 2020

In an interview with news outlet Jahanesanat, Adel Talebi, the Secretary of Iran’s Internet Businesses Association, expressed concern about the impact that internet outages would have on the entrepreneurship is needed to salvage Iran’s failing economy.

“Startups … have no way of facing the challenges of internet disruption,” he said. Talebi went on to note that the trend, if normalized, would undoubtedly contribute to Iran’s ongoing “brain-drain” of elites and professionals.

Meanwhile, those who cannot emigrate may be irreparably harmed by their lack of access to reliable internet service. As state outlet Entekhab reported, for the 200,000 e-commerce retailers in Iran, internet blackouts completely obstruct their sole means of livelihood.

Regime’s Internet Paradox

Blocking the internet also has the vital effect of slowing the spread of information about human rights abuses that the regime commits as part of its broader strategy for stamping out dissent. While this may benefit Iran’s leaders momentarily, it also draws the international community’s attention while further inflaming the Iranian people’s resentment for a government that has so badly mismanaged their economy.

And because internet blackouts come with steep economic costs, they cannot be maintained over the long term. As a result, when they inevitably come to an end, the regime suffers from an outpouring of communication between and among Iranian dissidents and foreign adversaries. This, in turn, reinforces the perceived need for tight control over online communication, in what threatens to become a never-ending cycle.

Of course, in reality, that cycle cannot continue forever. It must lead to one of two outcomes.

Either Tehran will succeed in the taunting technical feat of cutting off Iran from the global internet without losing its economic benefits, or the regime that depends so thoroughly on the absence of communication will collapse at the hands of an informed and tech-savvy population.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.