COVID-19 hit the US big time in mid-March, so we’ve now had about three months to assess how litigants, courts, and election officials are planning to handle upcoming elections. In most of the country, officials have stood up for voting rights, as many states have quickly made voting-by-mail easier and more available. But a few states and some right-wing outside groups have resisted that common-sense change and have insisted that most voting will be done in person, pandemic be damned.

These states – let’s call them the “Intransigents” – are now being forced to defend their refusals in court. Their defenses haven’t gotten much press, but the arguments are disturbing.

The Intransigents have defended their refusals to expand absentee voting with the bizarre argument that restrictions on voting by mail do not implicate the right to vote at all. Amazingly, a three-judge panel of federal appellate judges in New Orleans recently bought the argument. For the sake of our republic, no other court should.

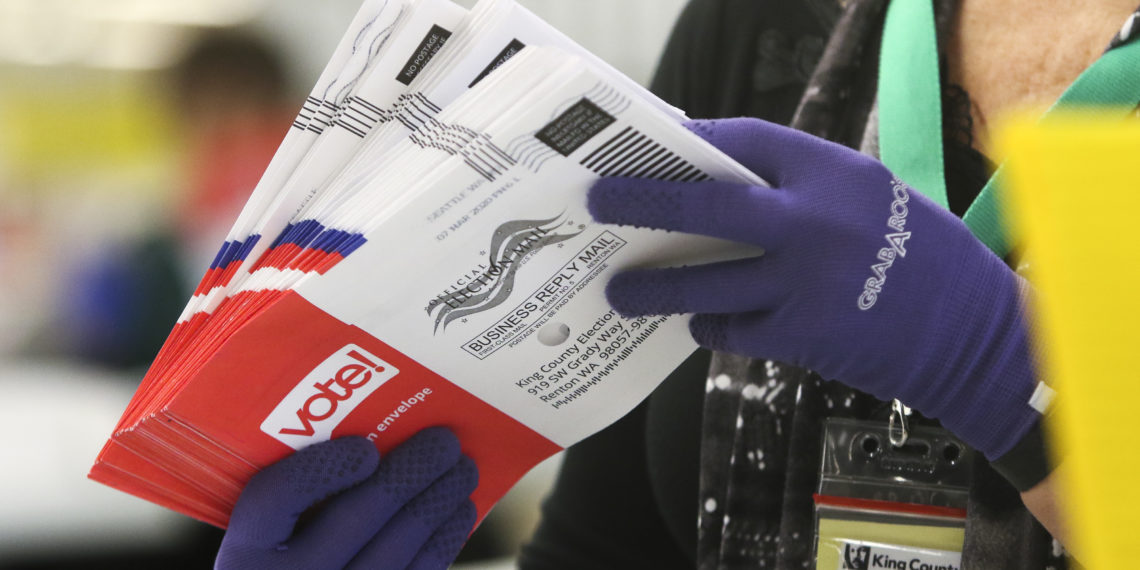

Voting By Mail

Here’s the lay of the land from where we sit in 2020. We are faced with a pandemic headed into an election that is, well, pretty darn important. Fortunately, we have a safe and secure tool to be able to run elections while also complying with physical distancing requirements: absentee balloting, also known as voting by mail or voting at home.

This is not new. In fact, absentee balloting has been around in a substantial way in America at least since the Civil War, when postal voting first became both necessary and common.

By 1924, at least 45 of the 48 states permitted absentee voting, but it was still relatively uncommon in the first half of the 20th century. In 1936, one estimate was that 2 percent of all ballots were cast by absentee ballot. By 2000, that was up to 14 percent, and, in the last midterm election in 2018, over 25 percent of all voters voted by mail.

Unsurprisingly, data from this spring’s elections show that number is about to surge. In Georgia, where voting by mail was used by around 6 percent of voters in 2018, it was used by 50 percent of voters in the June primary.

For the primaries held on June 2, use of absentee ballots or vote-by-mail went from 100 percent in Idaho and Montana – which held all-mail elections – to 58 percent in South Dakota. Maryland saw an astonishing 93 percent percentage point rise in mail balloting relative to the 2016 primary: from 4 percent to 97 percent.

Increase in Absentee Balloting

The stunning acceleration has, of course, been a result of the difficulties of voting in a pandemic. But it’s important to recognize that it’s not just the pandemic that has led to this increase. Even before this year, voting by mail had gone from a useful option for a small set of people to a key part of the right to vote. This change happened through both legislation by Congress and the expansion of absentee voting in every state.

Congress has, on at least two separate occasions, recognized that absentee balloting is part of the “right to vote.” First, in 1970 amendments to the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, Congress ensured that voters away from their state or who had moved very recently could vote for president by absentee ballot.

In so doing, Congress found that “the lack of sufficient opportunities for absentee registration and absentee balloting in presidential elections … denies or abridges the inherent constitutional right of citizens to vote for their President and Vice President.” With the stroke of a pen, absentee balloting went from a choice to a requirement. It became a key part of the “right to vote.”

Later, in 1986, Congress passed the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act, which again placed absentee balloting squarely within the “right to vote.” That law requires states to, upon request, provide absentee ballots to military voters and their families stationed away from their normal residence as well as to Americans living overseas who are qualified to vote in federal elections.

In a later amendment to that law, Congress noted that state officials “should be aware of the importance of the ability of each uniformed services voter to exercise the right to vote” via absentee ballot.

Right to Vote

States have followed Congress’s lead and greatly expanded access to ballots that can be voted at home rather than at a polling place.

In a majority of states, voters in the upcoming election will be able to vote at home for any reason. A few states (Oregon, Washington, and Colorado) even run elections that are essentially mail-only. In fact, according to the Brennan Center, voting at home was used by a majority of voters in nine states, and they’re a diverse bunch: the over-50 percent club includes left-leaning California and Hawaii but also two of the most Republican states in the country, Utah and Montana.

Overall, mail ballots were used by more than 1 in 4 voters in 2018. In the presidential election, it is nearly certain that at least 50 percent of votes will be cast by mail ballot – maybe even more than that.

“Try it, you might like it.”

Oregon’s Republican Secretary of State, Beverly Clarno, responds to President Trump’s claim that vote by mail is dangerous and subject to fraud. Oregon pioneered the practice in 1998. https://t.co/jZuELMAKYJ pic.twitter.com/Y8TjsKyiGK

— 60 Minutes (@60Minutes) June 28, 2020

All of this should lead to but one conclusion: of course voting by mail is part of the “right to vote.” Absentee ballots are required by federal law for certain voters; they are used by a majority of voters in nine states; most Americans will not even go to a polling place this year.

This is an important conclusion because placing voting by mail within the legal “right to vote” has an important legal consequence: states have to tread carefully and be particularly even-handed when they impose burdens and provide benefits.

Restrictions on the right to vote, after all, get close looks by courts who are supposed to ask tough questions about these laws. Are they applied equally? Do any laws make it too difficult for certain people to exercise their cherished right to vote? Do they impose disproportionate burdens on one particular race? Religion? Geographic group? Age cohort?

Given the recent legal changes and surge in mail voting, you would think that all courts would be asking these questions about restrictions on voting by mail, which clearly impact the “right to vote” (the word “vote” is right there in both phrases, after all). You would even think that states would concede this point, and attempt to meaningfully justify their restrictions as critically important to, say, safeguard elections or ensure all voters are treated equally.

But oh, dear reader: you would be very, very wrong. In some states and some courts: of course. But not in Texas. Not in Tennessee.

Right to Vote as Privilege

The Intransigents look at voting differently than the rest of us. To them, the right to vote is a privilege, like membership in a private country club with perfectly-kept tennis courts, just washed and scrubbed and waiting for those finest members of society to come by and start a game.

To these states, so long as everyone can vote somehow, somewhere, the state can make it as easy as it wants for any particular subgroup to also have the additional option to vote by mail. And if it turns out that it’s really easy to vote by mail for older, whiter, more Republican-leaning voters, but it’s harder to vote by mail for younger voters, people of color, and those who lean Democrat – oh well! Those people just aren’t invited to the vote-by-mail country club.

But don’t worry: those voters are more than welcome to use the public voting machines. They just may need to stand in line for a while. And they might risk getting COVID. And they might have to leave their job early, or forgo pay, or find childcare. But hey: they can still vote, and that’s the important thing!

Lest you think this is a cruel joke, let me now begin quoting from actual legal briefs and decisions. You may want to sit down for this part.

Intransigent Texas

Let’s start in Texas. Texas, as an Intransigent, has fiercely resisted efforts to make it easy for most people to vote by mail, with one exception: it will happily follow a state law allowing anyone 65 or older to vote by mail for any reason or no reason at all. Plaintiffs in federal court pointed out this preference for older voters is blatantly unconstitutional. After all, we have a constitutional amendment – the little-used 26th Amendment – that specifically says that the “right to vote” cannot be “denied or abridged on account of age” for any voter 18 or older.

That means Texas can’t make it harder for younger voters to vote absentee than older voters. A federal district agreed with them, but its injunction permitting broader access to absentee ballots was put on hold by a three-judge panel of conservative federal judges that bought Texas’s bizarro theory.

Here’s the upside-down reasoning. The court first looked to a 1969 Supreme Court case called McDonald. In McDonald, the plaintiffs were two Illinois men who were in jail pending trial and were denied absentee ballots, and the Supreme Court upheld that denial, even though others in Illinois, like those “physically incapacitated” for medical reasons, would have gotten absentee ballots. On the basis of this one case, the federal court reasoned that Texas could allow anyone it wants to vote absentee: every citizen is like those citizens awaiting trial, able to vote by absentee ballot only if the state deems them worthy.

In the court’s words: “The plaintiffs” – that is, younger voters – “are welcome and permitted to vote, and there is no indication that they are in fact absolutely prohibited from voting by the State.” Therefore, when it comes to absentee voting, “the right to vote is not at stake.”

In other words: older, whiter voters have the country club, vote-by-mail option if they want it. But younger voters can only use the public courts. And there’s no problem with that, because, well, the case isn’t even about the right to vote at all.

Age-Related Disparities

Sadly, this argument is proliferating among the Intransigents. A few days after the decision, the state of Tennessee told its state supreme court to reverse a lower court order requiring broad access to absentee ballots, and it put forth the same bizarre reasoning that regulations regarding absentee voting are not about the right to vote.

Its legal brief contained a truly remarkable admission about how impactful its theory is: because that state, too, permits older voters to vote by mail without any excuse but has a different standard for younger voters, Tennessee is preparing for 100 percent use of absentee voting by voters 60 and older and less than 6 percent absentee voting by voters under 60.

It is hard to find reliable statistics, but, if that holds, it may be the starkest age-related disparity in voting in the history of American elections.

The seven states that generally discourage voting by mail but waive excuse requirements for Republican–leaning old folks are Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas…all deep-red states carried by Trump in 2016… https://t.co/CLauPXNUho

— Nope. (@JoyAnnReid) April 10, 2020

And the hits keep coming. Alaska recently announced that it will mail absentee ballot applications only to voters 65 and older but not younger voters. Missouri just amended its law to permit older voters to vote by mail easily, but younger voters need their absentee ballots notarized (good luck finding one of those!). It’s possible more will come as the election season wears on.

But the real tragedy is, if this reasoning gains traction, age is just a start. If the right to vote is not even at stake when it comes to regulations around voting by mail, could states provide postage to rural voters and not city voters? Could states make Native American voters living on reservations mail their ballots in before election day but go door-to-door in the suburbs to pick up completed ballots? The list of possible discrimination goes on. It’s a scary list.

Voting During Pandemic

The Plaintiffs in the Texas case took an emergency appeal to the US Supreme Court, so there is a chance for that awful decision to be wiped off the books like a bad memory. It should be. After all, it is easy to distinguish the McDonald case. That case said the outcome would have been different if members of a suspect class other than “pretrial detainees” were discriminated against. The Supreme Court in that case mentioned wealth or race as suspect classes because the case was decided before age was specifically added when the 26th Amendment was passed in 1971, but age should surely be on the list now too. The appeals court just decided to conveniently ignore that feature of the case.

As importantly, that case was decided before Congress enshrined the right to vote by absentee ballot in several federal laws, before voting by mail became a key part of US elections, and before a global pandemic will make voting by mail the way most Americans actually cast their ballot.

And the McDonald case also said that the restrictions were valid because there could have been other ways for those inmates to vote. But it’s not at all clear that in 2020 many Americans will have a safe and secure way to vote in person, given the combination of poll-worker shortages and the justified fear people have of contracting and spreading COVID. So this case is unlike McDonald in no fewer than six ways. The Texas court just ignored all the differences.

Still, while we wait to see whether that case will be overturned, let’s end with some hopeful news.

Despite the existence of a few Intransigents who think otherwise, most government officials have recognized the new normal is voting by mail. Voting by mail, for most people in most states, is thus inseparable from the right to vote. Let’s just hope the Supreme Court gets the memo.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.