Why have assessments of national capacity to respond to infectious disease so seriously missed the mark in predicting how the US and other countries would respond to the COVID-19 pandemic?

One significant reason is that they have failed to appreciate the role of effective leadership.

In the aftermath of Ebola, Zika, SARS, and other diseases, several indices and assessments were developed to measure governments’ strength and capacity to predict their ability to prevent and respond to the next epidemic.

These indices predicted that several countries would effectively respond to such issues, most notably the US and Brazil. However, the US currently has the world’s highest number of COVID-19 cases and deaths. Brazil’s death rate has surpassed 88,000, second only to the US and significantly poorer than predicted.

Government Capacity and Leadership

These indices are well-designed and comprehensive in their assessment of risk. They rightly consider not only state capacity but other indicators that can hinder or improve a government’s response. They also rely on conflict and fragile state watch lists and worldwide governance indicators, including forced migration, competition over resources, unresolved group grievances, corruption, and violent attacks.

The governance indicators focus on control of corruption, the rule of law, civil liberties and political rights, government effectiveness, and political stability.

However, there is a fundamental assumption in these indices that government capacity equates to government competency. The designers of these indices assumed, common to some political science models, that part of the function of government capacity is the selection of competent leadership.

….Together we are putting into policy a plan to prevent, detect, treat and create a vaccine against CoronaVirus to save lives in America and the world. America will get it done!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 11, 2020

Hence, governments with extensive institutional capacity will choose to use those resources in a well-reasoned and responsible fashion. The US and Brazil’s response, particularly at the federal level, shows this assumption is flawed. The failures have not come from institutional design, but from failures made at the level of the individual political leaders.

Good political leadership is ultimately a question of an individual’s decisions, and it is necessary to identify, flag, and factor the possibility of severe flaws in potential political decision-making.

Slow US Response to COVID-19

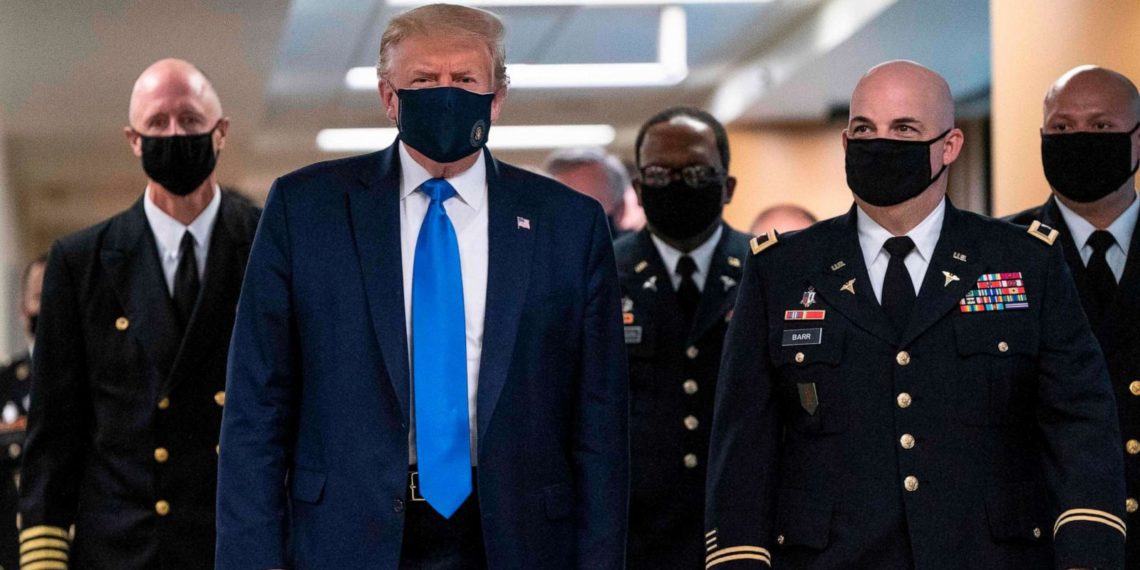

The US federal government’s slow response can be directly attributed to themes that stretch throughout the current administration. For example, President Donald Trump appears focused on questions of narrative: concerned more about managing the collective perception of navigating fault away from his administration rather than accepting evidence-based analysis of how to address problems.

Findings that do not support Trump’s administration’s decisions or narratives, even those from within the government by career civil servants, are often attributed to partisan politics and a deep state rather than dispassionate analysis.

The US government is increasingly politically factionalized, seeing all issues or problems as a zero-sum game in which their party must be the winners and other parties the losers. This political factionalism and politicization of any government must be heavily weighted in any methodology because it is a significant contributor to the US’ inability to stop the spread of COVID-19 and threatening the greater stability of the country.

Brazil’s Destabilizing Response

The US is not the only government where political leadership is threatening a country’s effective response to the pandemic.

Brazil has a highly developed public health system and scored well on the indices in advance of COVID-19. Although cuts to the healthcare system have left it vulnerable, President Jair Bolsonaro’s denial of COVID-19 is a seriously destabilizing factor to Brazil’s pandemic response.

The president claims the virus is just a “fantasy,” accused the media of creating fear, and fired the health minister when he warned the health system could collapse soon. These decisions – attributable specifically to President Bolsonaro and his attempt to manage the disease’s narrative rather than the details – mirror the response of leadership within the US with correspondingly poor results and increasingly leading to destabilization.

Indices which attempt to measure institutional capacity must include and seriously weigh political leadership risk and political factionalism in a more intentional and nuanced way.

The gap between the high ratings of the US and Brazil’s institutional capacity and their national government’s performance shows that political leadership, even in a robust democracy, can lead to illogical and disastrous decisions that significantly impact a countries’ response and override all other positive indicators.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.