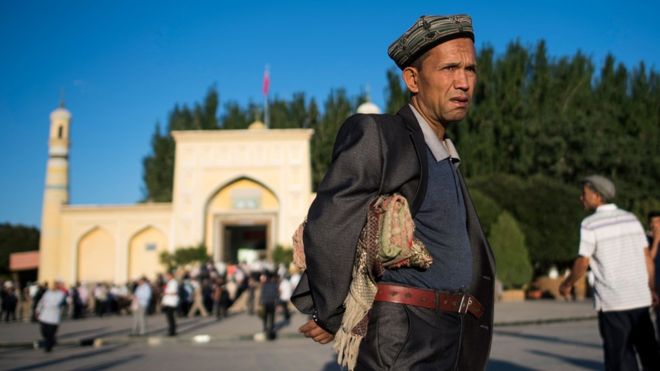

It is now beyond doubt that China is undertaking a program of mass incarceration of the Uighurs population of its far north-western province of Xinjiang (which many Uighurs refer to as East Turkestan) in “re-education” centers.

Analysis based on Chinese government procurement contracts for construction of these centers and Google Earth satellite imaging has revealed the existence of hundreds of large, prison-like facilities throughout Xinjiang that are estimated to hold up to 1 million of the region’s Turkic Muslim population. One of the largest facilities, Dabancheng near the regional capital Urumqi, alone is estimated to have a capacity to hold up to 130,000 people.

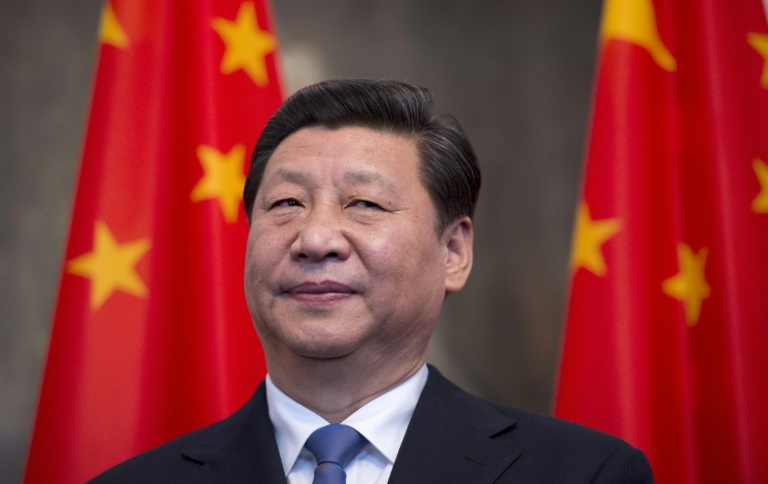

In these facilities, detainees experience a regimented daily existence as they are compelled to repeatedly sing “patriotic” songs praising the benevolence of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), study Mandarin, Confucian texts and President Xi Jinping’s “thought,” and endure regular physical violence and torture.

Beijing’s Justification

After previously denying their existence, Beijing has begun to mount a defense of this system of mass incarceration in the name of counter-terrorism.

China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi, speaking after meeting with Germany’s foreign minister in Beijing on 13 November, asserted that China’s approach in Xinjiang is “completely in line with the direction the international community has taken to combat terrorism, and are an important part of the global fight against terrorism.”

However, an assessment of the terrorist threat to Xinjiang and an exploration of the ideological and legislative underpinnings of the system of mass incarceration suggests Beijing is using counter-terrorism as a pretext to conduct a form of “cultural cleansing” of the region’s Turkic Muslim population.

This amounts to a cautionary tale in the global “war on terrorism” whereby an authoritarian state has eagerly instrumentalized the threat of terrorism to enhance its control over a historically-contested frontier region and distinctive ethnic minority population.

From Splittism to Terrorism

While Beijing claims the region has been an “integral” province of China since the Han dynasty (206 BCE–24 CE), it often remained beyond Chinese control due to its geopolitical position as a “Eurasian crossroad” abutting present-day Russia, Central Asia, Afghanistan, and Pakistan and the ethnocultural dominance of Turkic and Mongol peoples.

Since the People’s Liberation Army “peacefully liberated” the region in October 1949, the Chinese Communist Party has been consistently focused on overcoming the historical barriers to consolidated Chinese control: geographic remoteness from the center of Chinese power; economic underdevelopment; and ethnocultural dominance of non-Han ethnic groups.

To overcome these barriers, Beijing has pursued an aggressive strategy of integration characterized by tight political, social, and cultural control, encouragement of Han Chinese settlement, and state-led economic development backed by repression of overt manifestations of ethnic minority opposition.

China is abusing rights in Xinjiang on a massive scale:

13 million people subjected to forced political indoctrination & mass surveillance;

Est. 1 million people in "political education" camps;

1 million+ officials & police officers monitor people https://t.co/4tlRg8rhIP pic.twitter.com/EDh0GveOQg

— Human Rights Watch (@hrw) September 10, 2018

This has stimulated periodic violent opposition from the Uighurs population who have bridled against demographic dilution, political marginalization, and continued state interference in the practice of religion.

Until the late 1990s, the Chinese state framed this as “splittism” or “separatism” inspired by ethnic nationalist aspirations for an independent East Turkestan. The attacks of 9/11, however, enabled Beijing to reframe this as “terrorism.”

This began immediately with Beijing releasing its first documentation in January 2002 of “over” 200 alleged “terrorist incidents” between 1990 and 2001 perpetrated by a previously unknown group, the “East Turkestan Islamic Movement.” While this group appears to have functioned in Afghanistan from 1998 to early 2000s, it was a small and marginal group that had little ability to strike Xinjiang.

A number of high-profile incidents in more recent years such as the October 2013 SUV attack in Tiananmen Square and the April 2014 Kunming railway station mass stabbing attack, and evidence of a Uighurs presence in Syria has reinforced the official narrative that China faces a genuine threat stemming from Xinjiang and embedded counter-terrorism as a national security priority.

‘Eradicating Tumors’

This has resulted in a variety of security and legislative changes both at the national and provincial level since 2015.

In the security context, the regional government’s expenditure on public security ballooned in 2017 amounting to approximately US$9.1 billion, a 92 percent increase compared to 2016.

Much of this expenditure has been absorbed by the development of a pervasive, hi-tech “surveillance state” in the region, including the use of facial recognition and iris scanners at check-points, train stations and gas stations, the collection of biometric data for passports, mandatory apps to cleanse smartphones of potentially subversive material, and the use of surveillance drones.

Over the past three years, there have also been significant legislative counter-terrorism measures adopted including China’s first national counter-terrorism law in December 2015 and Xinjiang regional government regulations on “de-extremification” of March 2017.

The latter of these is particularly revealing of the logic and intent of current Chinese policy. According to these regulations, “extremification” refers to “speech and actions under the influence of extremism, that imbue radical religious ideology and reject and interfere with normal production and livelihood” and can include fifteen “primary expressions” of extremist thinking, including “wearing or compelling others to wear gowns with face coverings, or to bear symbols of extremification,” “spreading religious fanaticism through irregular beards or name selection,” and “failing to perform the legal formalities in marrying or divorcing by religious methods.”

This, as Newcastle University expert on Uighurs culture Joanne Smith-Finley argues, has seen the state “securitize all religious behaviors, not just violent ones,” leading “to highly intrusive forms of religious policing” that violate and humiliate Uighurs.

There is therefore little doubt that the Chinese Communist Party clearly identifies “extremism” as inherent to everyday markers and practices of the Uighurs profession of Islam and has effectively securitized Uighurs identity itself as an almost biological threat to the health of Chinese society.

As such, to be successful, “de-extremification” must fundamentally transform Uighurs identity. Some recent statements of government and party officials confirm this, with some describing Uighurs “extremism” as a “tumor” to be eradicated and Islamic observance as akin to drug addiction.

Cure Worse than Disease

Significantly, there are clear indications that China intends its policies of “de-extremification” to be in place for the foreseeable future. Most notably, there is evidence of China rapidly expanding the number and size of the “re-education” centers in Xinjiang.

Chinese officials have also explicitly noted, and defended, the need for these measures to endure. A Chinese Communist Party Youth League official in Xinjiang, for instance, warned in a speech in August this year that the party had to be “cautious” in assessing the success of its “de-extremification” efforts as:

…having gone through re-education and recovered from the ideological disease doesn’t mean that one is permanently cured. We can only say that they are physically healthy, and there is no sign that the disease may return. After recovering from an illness, if one doesn’t exercise to strengthen the body and the immune system against disease, it could return worse than before. So, after completing the re-education process in the hospital and returning home … they must remain vigilant, empower themselves with the correct knowledge, strengthen their ideological studies, and actively attend various public activities to bolster their immune system against the influence of religious extremism and violent terrorism, and safeguard themselves from being infected once again, to prevent later regrets.

More senior Chinese officials have also publicly defended and justified this approach. Vice Foreign Minister Le Yucheng, for instance, strenuously defended China’s approach in Xinjiang in his statement at the “periodic review” hearing of China’s human rights record before the United Nations Human Rights Council on 6 November. He pointedly dismissed international criticism of the “re-education” centers as “politically driven accusations from a few countries fraught with bias” before referring to detainees as “students” who attend the centers on a “voluntary” basis eager to learn how to “inoculate” themselves against “extremism.”

As far as Beijing is concerned, then, its measures in Xinjiang are a justifiable form of “preventative” counter-terrorism.

Beijing has thus arguably embarked on a programme of “cultural cleansing” in Xinjiang as means of eradicating what it has come to perceive as an unacceptable threat to the security of the state, regardless of the reputational costs it may suffer internationally in the process.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.