The cliché that real life is often stranger than fiction has exactly matched the outcome of the first round of Ukraine’s presidential election, where the young comedian-turned-

It turns out that the Ukrainian youth is an excellent barometer for the country’s broader domestic political climate. While seasoned political observers were surprised by the first round’s outcome, the attitude, trends, and online engagement patterns of Ukrainian youth have proven to be effective indicators of what was in the cards. Tracking, monitoring, and analyzing these trends could serve as an excellent “insurance” against such surprises.

For the past six months, a group of students from the University of Texas has studied the role of youth engagement and political attitudes in Ukraine under the auspices of the university’s Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies. The project led by Professor Mary Neuburger includes a focus group, survey, and a study of social media use leading up to the elections.

The ongoing research has provided interesting data and interim analysis that can help to interpret the success of the unorthodox frontrunner of the so-called Komanda Ze, the platform on which TV comedian Zelensky runs for president.

What the ‘Servant of the People’ Got Right

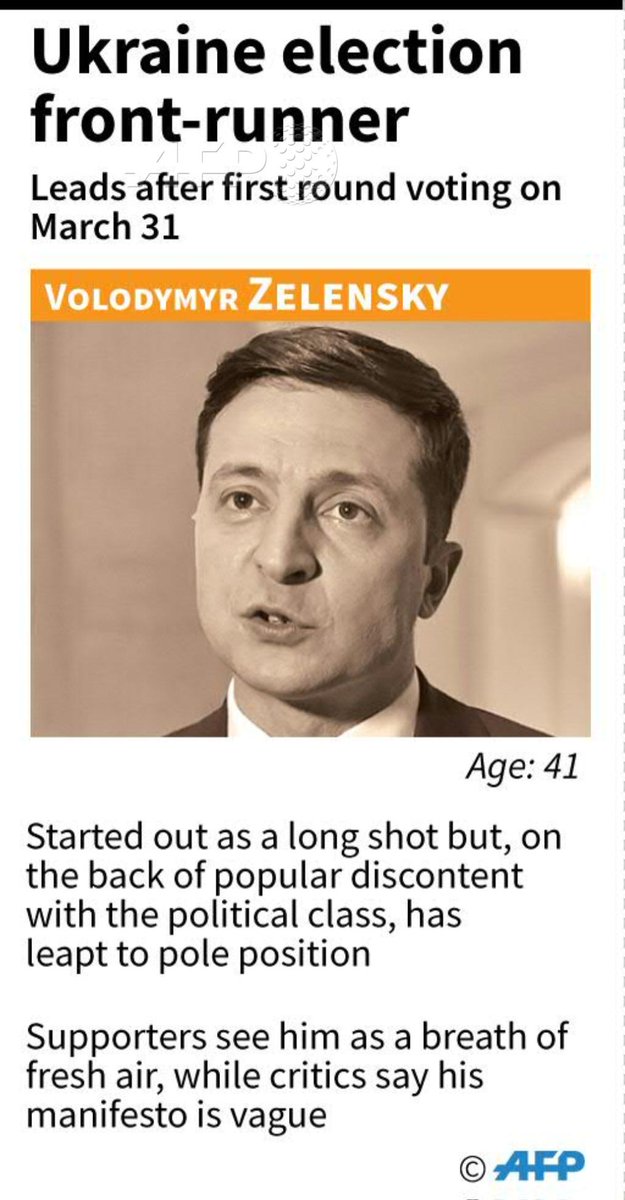

The 41-year-old comedian is an absolute newcomer to politics. His carefully crafted image is the complete opposite of all of the other establishment competitors such as incumbent President Petro Poroshenko.

Zelensky’s popularity stems from his comic stints and role as the lead character in the popular sitcom Servant of the People. In the TV show, Zelensky plays an ordinary high school teacher who is prompted by his students to run for president. The teacher wins the election, only to be saddled with the endless absurdity of corruption and nepotism tightly gripping the country.

Again, life can be stranger than fiction. Ironically, the real-life person behind the fictional “Servant of the People” managed to capture no less than 30 percent of the vote in the initial round of the presidential elections. A popular meme about Zelensky’s cabinet jokes that it would be staffed by TV and film characters, from Borat to Frank Underwood and James Bond.

Meanwhile, Ukraine is struggling with severe economic, demographic, and social challenges, while simultaneously fending off constant aggression from neighboring Russia.

What did the inexperienced newcomer to Ukrainian politics get right to corner his battle-hardened opponents? Interim data analysis about youth engagement and social media use indicates that Zelensky has been able to capitalize on his outsider celebrity status, media-savvy behavior, and slick tactical use of social media.

Most importantly, it was the craft and maintenance of a rather simplistic narrative focused solely on tackling corruption. This narrative has found a widespread audience but has been especially effective in mobilizing the Ukrainian youth who are stereotypically seen as apolitical, disengaged, and very cynical.

Zelensky has clearly sensed and capitalized on the youth’s sentiments. More precisely, on their frustration and fatigue with Ukraine’s slow and rocky “perpetual transition” to a full-fledged market economy and democracy, and Ukraine’s status of a troubled laggard in the European Union’s waiting room.

Zelensky’s celebrity outsider status made him the candidate most capable of benefitting from the youth’s generational discontent with the quality of governance and anger with the Ukrainian elites’ corruption – the very forces that led to the proliferation of their widespread cynicism, disillusionment, disengagement, and subsequent massive migration abroad.

Comedian-in-Chief’s Bag of Tricks

The interim analysis of the survey results points to several explanations as to why the political outsider was able to outsmart and out-campaign his highly experienced opponents.

First, Zelensky incorporated new platforms and tactics into his social media campaign. While, according to our survey, youth mainly use Facebook for political and civic activism, most Ukrainians (and, accordingly, less politically active ones) are more likely to be on Telegram and Instagram for communication and entertainment purposes. This explains why many of our focus group participants were reticent of the sudden politicization of Instagram though advertisements.

It’s critical to point out that Instagram and Telegram are more conducive to one-way information exchange and objectification of users than Facebook is.

Telegram, in addition to its basic messenger function, is built around channels, where creators often anonymously share content without any public displays of feedback or places for discussion.

Instagram, for its part, requires users to post photos or videos and is thus biased toward the visual, whereby the user is a passive object meant to receive entertainment content and not necessarily respond to it.

This differs these two platforms fundamentally from Facebook, which is first and foremost a textual medium where complex texts can be posted and discussed with less anonymity, and where users are social subjects who may participate in debates.

While Zelensky had a significant campaign presence Facebook, revolutionary were his vigorous campaign efforts on Telegram and Instagram, where Zelensky’s activity was much more visible than the other candidates. These two platforms allowed him to reduce messages to a simple image that potential voters received without any visible backlash or criticism, while on Facebook users would have been exposed to alternative opinions through more active and confrontational debate of the issues.

https://twitter.com/ianbateson/status/1110896343537602561

Second, Zelesnky was able to create a highly effective social media echo chamber resembling a hall of mirrors. His social media activity consists almost entirely of links to other Zelensky websites, such as the campaign blog which generates content including internal polling data and fan support.

Zelensky’s official campaign platform, for example, only links to his Facebook page, specifically, to videos of Zelensky. It does not link to facts, articles, or white papers supporting his policy positions (if you can call them that).

By sending potential supporters on a carousel of Zelensky content without links to other organizations, let alone the outside world, the campaign was able to capture and insulate voters from the negative press about him and the growing backlash to his frontrunner status.

Good News

The decisive second round on April 21 will determine Ukraine’s new political arrangements but will also have serious implications well beyond Eastern Europe. With this date quickly approaching, one can only speculate about the nature and specifics of the signals sent by the Ukrainian voters so far.

The good news is that the youth categorically don’t see Russia’s political system as an attractive model of governance for Ukraine’s future. In unprecedented and total unanimity in both the survey and focus groups, the United States political model was by far mentioned as the best for Ukraine, followed by those of Germany and the Baltic states.

While several Ukrainians eagerly mentioned the very real downsides of the ongoing conflict with Russia, including the loss of economic cooperation and cultural connection, they didn’t appear to be eager to give Russia any concessions to mend the relationship. This is quite astonishing given that the leading pro-Russian candidate in the election, Yuri Boiko, came in fourth place and received over two million votes in the first round, mostly from older and Eastern voters.

If this pro-Western stance is truly so strong amongst the youth, Ukraine’s eventual integration into the Euro-Atlantic community becomes not a question of if, but simply when. The West should prepare.

Bad News

The bad news is that much of the new engagement brought forth by Zelensky is largely misinformed. Zelensky is not only a symptom of mass societal cynicism but also the result of a gross lack of knowledge among Ukrainians about the country’s electoral system and governmental structure.

For example, few Ukrainians seem aware that the president nominates the prime minister and other governmental and regional ministers, but does not have any statutory competencies in the domestic sphere. His influence over the government, while significant, is largely informal. The prime minister is the head of the executive branch, and therefore, along with the cabinet consisting of 17 ministers, the one responsible for administering policy with regards to the economy, institutional reform, and combating corruption.

Zelensky symbolized someone outside the system and therefore capable of fighting corruption, but at least formally, he won’t be able to do this from the office he’s seeking.

Anger at corruption in Ukraine is so high that many are thinking, screw it, let’s go for Zelensky, the comedian with no policy platform. One voter says: “He may be a clown, but he’s not an idiot.” https://t.co/iy4XF8EUSv

— max seddon (@maxseddon) March 29, 2019

Through his very candidacy, Zelensky is exacerbating the misperception that the president alone, not his cabinet or the parliament, is the institutional vehicle for fighting corruption. This perpetuates expectations of future political power that encourages clientelist networks to coordinate their activities around a single dominant political machine: the president. This is the very thing Zelensky is supposed to be fighting against.

Generational Divide and Second Round

Ukraine’s generational divide is similar to the one present in many post-communist states, but Ukraine’s status as a buffer state between NATO and Russia make the stakes of this divide higher than anywhere else in the world.

The youth raised during the internet age is bumping heads with an older generation who largely grew up under communism and are resigned to low standards of interaction with state institutions. These intuitions may have been reformed, but are, nonetheless, in most cases the same as under the communist regime. That may explain why an astonishing quarter of our survey respondents said that Ukraine currently has the same political system as during the Soviet Union era.

Indeed, the 1996 Constitution, which has gone through various changes since its ratification, was simply “pasted” on top of the same corrupt institutional bureaucracies and enterprises of the Soviet times (such as police departments and document offices, state clinics and hospitals, and industrial sector). Through their daily interactions with these institutions, young Ukrainians feel that these institutions are not up to the Western standards.

Right now, it appears Zelensky is likely to win the second round on the backs of these optimistic young Ukrainians, ready to throw a monkey wrench into a government they feel has stagnated, and only later decide whether to laugh or cry.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.