In 2017, China began to construct a huge network of detention camps in its northwestern Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Over a million indigenous Uyghur and Kazakhs are currently detained without trial. China depicts these camps as benign “vocational training centers,” but testimonies reveal a brutal regime of political indoctrination and self-criticism sessions, over-crowded conditions, inadequate food, and physical torture.

Outside the camps, people are also required to attend political meetings and Chinese language classes. Passports have been confiscated, contacts abroad are highly restricted, and special permission is required to leave one’s home town. Religious restrictions are so stringent that the government has effectively outlawed Islam.

A high-tech network of surveillance systems has been erected to ensure compliance with the new restrictions. The children of those taken to camps are sent to orphanages, and China is also relocating “re-educated” adults, secretly sending them to prisons in northeast China.

Cultural Genocide

China depicts these measures as necessary to counter Islamic extremism, but the huge numbers involved, and the detention of many Uyghur cultural leaders – writers and poets, academics and publishers, singers and comedians – suggest that the camps are designed to eradicate local languages and cultures to remold the region’s peoples as secular and patriotic Chinese citizens. Uyghurs in exile are now calling the situation a case of cultural genocide.

As a long-term researcher of Uyghur culture, I will talk about the recent wave of disappearances of leading Uyghur artists in December 2018, among them her long-term collaborator and friend, singer Sanubar Tursun.

I first met Sanubar in the summer of 2000, just after the release of her first album, when she was at the height of her powers. As I traveled around the south of Xinjiang, Sanubar’s voice filled the town bazaars and rang out from local taxis and long-distance buses. She was an iconic singer, the finest of her generation, and she should have been treated as a national treasure, but the authorities were always suspicious of her influence and did their best to block her at every occasion.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0uV1DTf2BO4

Sanubar’s career overlapped with a troubled period in the recent history of her region. Soon after her rise to fame came the September 11 attacks on New York and America’s declaration of a “Global War on Terror.” In its aftermath, China proclaimed its own war on religious extremism and terrorism in Xinjiang, and the region’s descent into violence and repression began.

For Uyghur people, Sanubar’s songs expressed feelings that couldn’t be said aloud. She spoke to me about the care she took in selecting her lyrics, often setting contemporary poets. She was always cautious and tried not to push the limits set by the authorities, but she wanted her songs to speak to her audience, to her people. She understood her power over them and told me with immense pride about her concerts in the rural south, which drew audiences of thousands.

In 2009, I spent the summer in rural Xinjiang, and Sanubar came to visit. The whole village crowded into the family orchard to hear her sing. Even the mulla and the religious ladies came and sat as close to Sanubar as they could, listening with rapt attention. The village hospitality machine went into overdrive. Families fought for the privilege of hosting Sanubar. I lost count of the number of sheep slaughtered for the honor of being tasted by her lips.

She began to travel: giving solo concerts in Turkey, Europe, and the United States. She was sponsored by the Aga Khan Music Initiative and worked with top artists from neighboring regions. She performed at the Konya Mystic Music Festival, and she teamed up with the Chinese pipa virtuoso Wu Man and toured in China and internationally. Her celebrity was cemented by a season as a judge on the Xinjiang Voice of the Silk Road talent show.

Hardening of Xinjiang

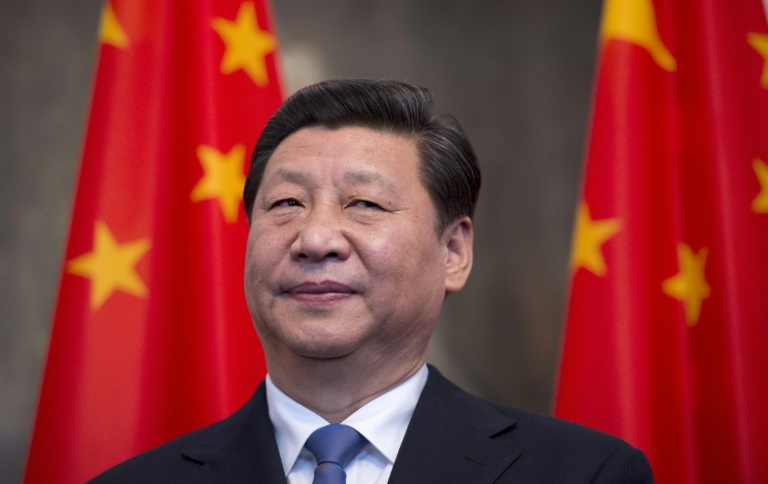

In 2016, as the political situation in Xinjiang began to harden, she began to turn down invitations to perform abroad. So many Chinese were now traveling abroad for study or tourism, but for Uyghurs, foreign connections were now suspect. As Xi Jinping’s “walls of steel” went up around Xinjiang, and its people were subjected to an intensive regime of surveillance and securitization unrivaled outside Gaza, I cut all ties with Sanubar, fearing that even a phone call might endanger her.

As news of the internment camps began to trickle out and we learned of the inclusion of leading artists and intellectuals among the million people detained, we could only hope that Sanubar’s celebrity might protect her. It now seems that hope was in vain. In December news began to circulate of her detention and a possible 5-year sentence. As usual, there has been no formal charge, not even an announcement of her detention.

From what we have learned of conditions within the camps, Sanubar is likely being held in an overcrowded and unsanitary cell along with up to 60 other women with space for sleeping only in shifts. Days are spent in a monotonous regime of singing Chinese revolutionary songs, studying Chinese language and the thought of Xi Jinping, and in self-criticism sessions in which they are required to denounce their own religion and culture.

Detainees are under constant surveillance, constrained to sit motionless, hands on desks, during 4-hour long study sessions. Failure to comply is punished by deprivation of food. There are harrowing reports of unknown forms of medication being forcibly administered, of violence and torture, of nervous breakdowns, suicides and deaths.

Not even the most violent extremist should be subject to the kind of treatment being meted out in these camps, but as Sanubar’s case makes absolutely clear, the mass detentions in Xinjiang are far away from the targeted response to Islamic extremism that the Chinese government claims it is pursuing.

Sanubar’s rapid fall from celebrity to internment camp came alongside a wave of reports of well-known artists being arrested. Those we have firm news of include the much-loved comedian Adil Mijit, veteran pop star Rashida Dawut, the young singer Zahirshah who came to fame through the Voice of the Silk Road TV program, and the veteran folk singer Peride Mamut whose cassettes of charming Kashgar folk songs brightened the post-Cultural Revolution scene in the 1980s.

Famous #Uyghur singers Senever Tursun(L),Parida Mamut(M),Aytilla Ala sentenced to 5 yrs each. Famous comedian Adil Mijit (R) who suspended from work arrested some days ago. Whereabouts unknown. #JusticeforUyghur #ConcentrationCamps #EastTurkistan #reeducationcamps https://t.co/rd8ee0VYQc

— Uyghur from E.T☪ (@Uyghurspeaker) December 15, 2018

We can draw two conclusions from this latest roster of detentions. Firstly, that no Uyghur is safe from the camps however great their celebrity or popularity. The levels of terror within the region are such that no protest and no opposing voices can possibly be raised there. Secondly, it is apparent that there is a deliberate policy of targeting cultural leaders: writers, academics, artists, adding weight to the charge of cultural genocide that is now being raised by Uyghurs in exile.

Sanubar has left a quiet international legacy, and I hope that the organizations who sponsored her and the audiences who enjoyed her music will not forget her. She released a CD in Italy poignantly titled Hope (Arzu), and her songs have been adapted for the Kronos Quartet.

I hope that wherever her music is played, people will use the opportunity to call on the Chinese government to release Sanubar Tursun and close down the internment camps in Xinjiang.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.