Watching the trials of the Catalan independentists now taking place at Spain’s highest court in Madrid, I have been reminded again and again of a scene from director Hal Ashby’s marvelous 1979 movie Being There.

The protagonist of that film, played by Peter Sellers, is a fiftyish man who has never ventured outside the confines of his birth home. His entire understanding of society has been exclusively shaped by television viewing.

When, upon the death of his father, this man-child is finally expelled from the dwelling, he roams the streets of Washington D.C. with his TV remote control unit in his hand. When he comes across sights that disturb him, he points the device at the offending scene the hopes of “changing the channel” of the reality before him. Needless to say, his efforts at discharging his anxiety through this mechanism are fruitless.

Handicap of Catalan Trials

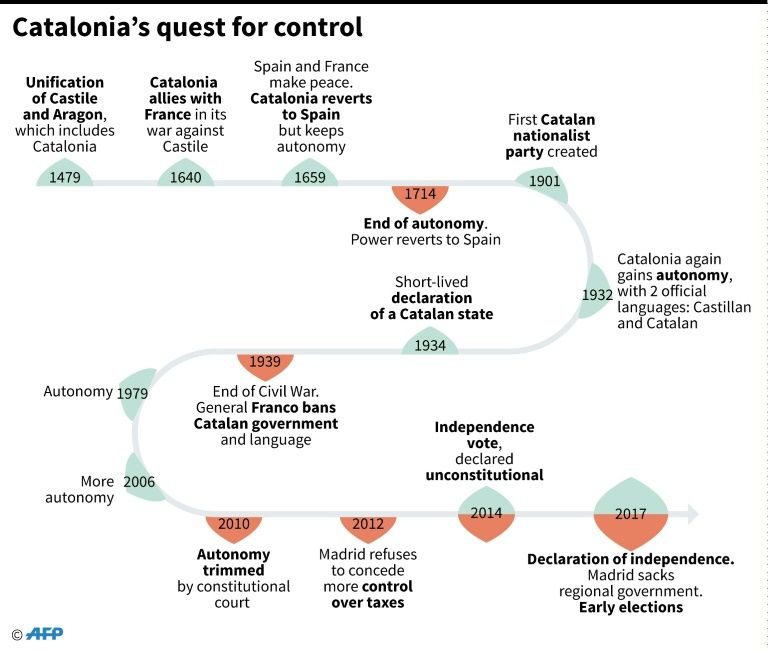

Each of the ten Catalan politicians and two civil society leaders currently sitting in the dock in the Spanish capital are there for allegedly having committed some combination of rebellion, sedition, and misuse of public funds. The Spanish prosecutors have been relentless in their attempts to underscore a narrative of events that will support the state’s allegations against these promoters of the October 2017 referendum on self-determination and the Catalan declaration of independence issued 26 days later.

However, they are doing so under a very severe handicap.

The empirical facts don’t remotely support their contentions.

And the Catalan defendants, most of whom have been held without bail for upwards of a year in violation of all existing judicial norms, are in no mood to play along with the game. Rather, they have convincingly refuted the serial exaggerations and mischaracterizations of their inquisitors point by point, often stopping along the way to give them eloquent lessons on the basic principles of participatory democracy such as the freedom of expression and the right to peaceably assemble.

Former government spokesman Jordi Turull even mockingly helped one black-robed eminence who – as a high-level prosecutor in an officially multi-lingual state – was struggling mightily to understand and pronounce extremely basic words from a document written in Catalan, a language quite close to Spanish in vocabulary and structure. Imagine the stupor it would cause if an Anglophone prosecutor at Canada’s Supreme court in Ottawa were unable to understand the words “cited” or “taken” in French. But in central Spain, the prosecutor’s patent ethnocentric ignorance did not provoke the slightest bit of embarrassment.

No Basis for Allegations of Rebellion or Sedition

Lest it seem that I am presenting things in an extraordinary slanted way, consider the following. The Spanish judiciary has twice issued European Arrest Warrants for former Catalan President Carles Puigdemont on the same charges now being levied against his former cabinet members and the two civil society leaders. And on both occasions – in Belgium in December 2017 and Germany in April 2018 – the European courts made clear through back channels to Madrid that they saw absolutely no basis for the allegations of rebellion or sedition. So, on both occasions, Spain hastily withdrew the requests in advance of the official announcements to save face before the rest of the E.U.

Although the German court did not rule out the possibility that Puigdemont could be extradited for misuse of public funds, Spain eventually dropped its extradition request on that charge as well.

Perhaps the decision had something to do with the fact that former Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy and his finance minister Cristobal Montoro – who had imposed a draconian auditing regime upon the Catalan Autonomous Government in the months leading to the 2017 referendum – both said publicly in its aftermath that the Catalan government had not spent a single cent on the vote.

In short, we have people being tried in Madrid for crimes that the Spanish government has been either unable or unwilling to pursue against the official most responsible for promoting the historic events in the Fall of 2017.

Francisco Franco and Spain’s Judiciary

So, why do these august jurists continue to click their remotes in the faces of the defendants?

Here’s why. Despite what you might have heard, and what many of us believed for a long time, the vaunted Spanish Transition to Democracy after dictator Francisco Franco’s death in 1975 was mostly a carefully managed piece of stagecraft. This was especially the case within the country’s judiciary.

For example, today’s National Court, where parallel trials against allegedly disloyal Catalan police officials will soon begin, started in 1941 as the Tribunal for the Repression of Masonry and Communism. In 1963, it was renamed the Tribunal of Public Order, and in 1977, in the midst of the Transition, it was given its present innocuous-sounding title. However, when that last change was made, its function and its personnel remained the essentially same.

For Franco, no political value superseded that of national unity. He thus created a judiciary that shared his belief that any and all means were justified in the fight to maintain it. And while the world became enthralled with the country’s enchanting “new” and seemingly democratic combination of modernity and high quality living in the 80s and 90s, the courts remained largely as they were during the dictatorship, with chances for ascent within the system carefully mediated by the need to sign off on the belief that national unity can and should trump the pursuit of impartial justice should the two values come into conflict.

Most knowledgeable observers believe that these sociological scions of Francoism will win the draconian convictions they seek against the Catalans. The question is whether the beleaguered democracies of Spain and the rest of the E.U. will be able to survive this great “victory” of deep state authoritarianism dressed up as the triumph of democratic constitutionalism.