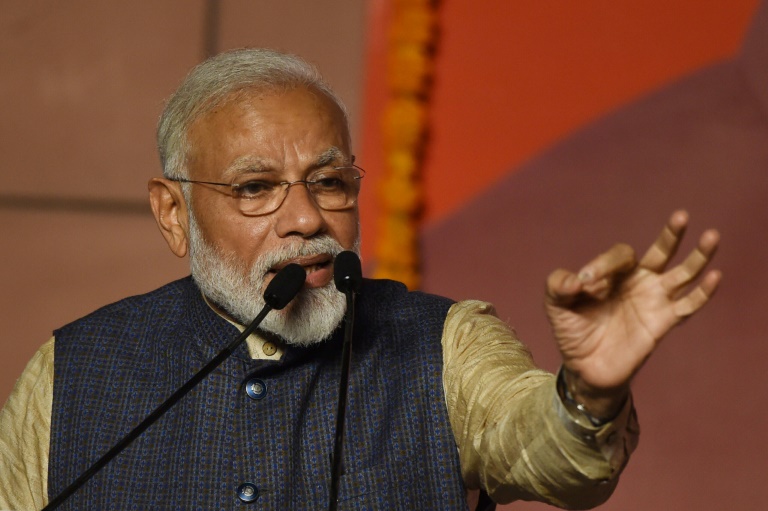

In late 2018, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated a colossal statue of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, one of the prominent leaders of the country’s freedom struggle. At 240 meters in height, the “Statue of Unity” is over two and a half times higher than the Statue of Liberty. It is also an apt simile for the magnitude of Modi’s triumph in India’s recently completed general elections.

A post-election survey conducted by the highly respected Centre for the Study of Developing Societies has revealed that the overwhelming victory of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was almost entirely due to voter support for Modi himself and not for his party. Although India is a parliamentary system and Modi is prime minister, in 2019 Modi transformed the contest into a presidential one.

India’s Elections and BJP’s Victory

The diverse parties which contested against the BJP hoped to secure victory by negotiating alliances and agreeing not to contest against each other. Failure to do so in 2014 had contributed to the BJP victory. In 2019, these once-reliable paths to power failed.

India’s traditionally fickle voters ignored high levels of unemployment, a flagging economy, and farmer distress – normally, a recipe for an anti-incumbency vote. The alliance’s calculations that voters belonging to large caste groups would vote along their predictable caste lines did not pay off either. When Modi told voters “Never mind who your local BJP candidate is, vote for me” in constituency after constituency, they did just that.

Above all, the opposition to the BJP failed to produce a leader who could match Modi in stature. Rahul Gandhi, president of India’s venerable Congress Party, campaigned tirelessly across the nation but failed to impress voters or gain traction with the party’s populist policies.

Modi Era

In a larger than life leader who is relatively young (age 68), India has found in Modi someone who may dominate the Indian political landscape for a decade or more to come.

This harkens back to the times of Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi, who also left presidential imprints on their respective eras. The Nehru-Gandhi era created a secular, socialist, non-aligned India in the image of the leaders of the time. We are now in the Modi era. What possibilities does it hold for the idea of India? This is a serious cause of concern for some, a cause for exhilaration for others.

Among those who cheer Modi’s ascent are Hindu nationalists who endorse a version of the “two nation theory” in which a Hindu India is seen as a mirror image of an Islamic Pakistan. These supporters would like to see a more muscular and assertive Hinduism, released finally of the psychological burden of a “thousand years of foreign (read Muslim) domination;” an India which wrests back its Hindu history by repossessing city names and monuments with a Muslim past, strips religious minorities from the religion-based personal law practices they currently enjoy (why should the Muslims have a right to have up to four wives?), and seeks a more permanent merger of Kashmir with India by abrogating of its special constitutional status.

The critics of Modi fear the loss of Nehruvian liberal secularism. Though it was always more an aspiration than a reality on the ground, supporters hoped India would gradually grow into it, in the same way it has grown into a stable democracy – something many observers, at India’s inception, doubted it ever would. These contrasting notions of India have existed ever since, indeed even prior to, Indian independence. But this time the situation is different.

Modi’s stature, converted into his party’s electoral success, has given his larger coalition of like-minded allies a two-thirds majority in India’s lower house of parliament, the Lok Sabha, and in a few years will lead to a similar majority in the upper house, the Rajya Sabha. Once this happens, there will be few hurdles in the way of Modi to mold the idea of India to his liking.

Challenges Ahead

The coming years pose daunting challenges both for Modi and for the opponents of the BJP. Modi will need to consider what his historical legacy will be. More announcements of bold programs, which turn out to lack follow-through after the initial photo opportunities, will not suffice.

Can he make a serious dent in India’s poverty, especially in the countryside; can he resolve decades-old border issues with Pakistan and China? Above all, can the man whom TIME magazine recently labeled as “India’s Divider in Chief” bring development and reconciliation to India’s sizeable non-Hindu population, especially its Muslims?

What can India’s opposition parties do to counter the colossus which Modi has created of himself and thereby his party? Can they find a person of sufficient stature to stand as rival and potential alternative to Modi? Can the venerable Congress Party re-invent itself with policies and as an organization capable of defeating the BJP which has crushed it in a majority of Indian states?

While no one can predict events in the next five to ten years, one thing seems certain: Narendra Modi so overshadows the political landscape in India that this indeed is “The Modi Era.”