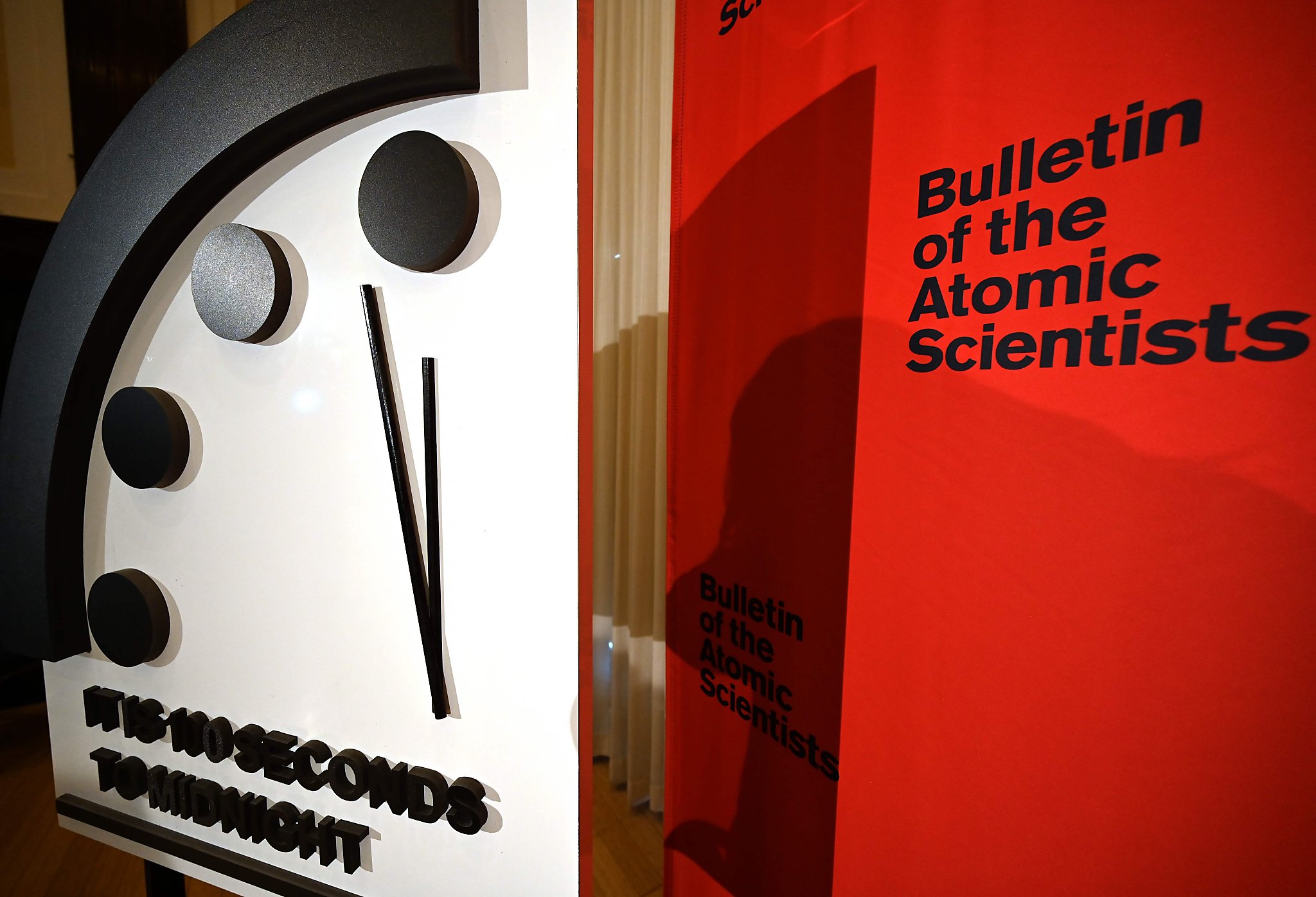

The hands of the Doomsday Clock are closer than they have ever been to midnight. First set in 1947, the clock was conceived by the editors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, a journal dedicated to exploring and understanding technological threats to humanity in the aftermath of the Second World War and the dawn of the atomic age.

The clock is a striking visual and temporal representation of humanity’s collective proximity to the apocalypse. The time now stands at 100 seconds to midnight, a full 20 seconds nearer than it stood in 1953 and 2018, which by the clock’s own metric were the most dangerous points since its inception.

If the “Elders” – the coven of magi by whose opaque methodology the clock is set – are to be believed, we should batten down the hatches. The end is nigh, and there’s very little we can do about it.

Threats to Humanity

This is not a Panglossian dismissal of the cataclysmic threats we face. Regardless of the narrative that pop-psych neoliberal evangelists like Steven Pinker are so keen to sell, it is not at all clear that the arc of human history bends towards progress.

Precarious improvements in material living standards for much of the world’s population do not indicate that free-market capitalism has saved us from the danger of human extinction. The news on climate change is dire – indeed, it could scarcely be worse.

Nuclear weapons, traditionally the Bulletin and clock’s primary concern, still exist in quantities enough to wipe out humanity several times over, and last year’s scrapping of a landmark arms control treaty further destabilized an already volatile geopolitical environment.

Nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, and antibiotic resistance also lurk in the future’s shadow.

The Elders will have taken these and a plethora of other threats into account when setting the “time.” Their concerns are well-placed. The clock, however, is a singularly unhelpful cipher by which to make sense of our planetary predicament.

Arbitrary Minutes and Seconds

For one thing, the clock is a remarkably unscientific medium for representing civilizational threats. Its minutes and seconds are essentially arbitrary: for its first appearance in 1947, it was set at seven minutes to midnight because this was the orientation that, to the designer Martyl Langsdorf, “looked good” (although, to her credit, it did).

It is strange then that we are asked to take the Elders’ word that a carefully considered methodology is behind each decision to inch the minute hand forward or back. Indeed, that the passage of time over the past two years has slowed to a crawl, advancing by mere seconds rather than minutes, suggests rather unflatteringly that those in charge have simply run out of space.

Perhaps this is forgivable. After all, the clock’s architects never imagined that it would be asked to visually represent the mind-boggling range of hypothetical Armageddons that we now think conceivable.

The Doomsday Clock was intended as a simple visual metaphor for nuclear danger. Arguably, however, it has failed even at this more modest task. As nuclear scholar Benoit Pelopidas points out, the logic of the clock chimed with the early Cold War belief that nuclear weapons would inevitably proliferate among a steadily greater number of states, thus moving the world closer to nuclear apocalypse.

In reality, nuclear proliferation has not progressed at the rate widely predicted at the dawn of the atomic age. Nevertheless, Pelopidas argues, “the permanence of a desire to imagine a history oriented toward proliferation” has allowed the clock to survive beyond its useful lifespan.

Doomsday Clock Is Obsolete

So, the Doomsday Clock is obsolete. It is a misleading and drastically oversimplified way to visually display the challenges we face, and its animating logic just doesn’t stand up. This is bad news enough.

Behind it, however, lies a more fundamental political problem. The image of a clock counting down to midnight imbues planetary threats with a quality of inescapability. Sooner or later, all clocks strike twelve.

The Doomsday Clock tells us that our fate is out of our hands, and although we are in the collective fight of our lives, this is simply not the case. Apocalypse is political, not inevitable. We need to wrest agency back from the grim mechanism of the clock.

Systematic Change

Seventy percent of greenhouse gas emissions are attributable to 100 corporations. We can identify the climate culprits. As fires, melts, and unprecedented die-offs hammer home the terrifying realities of climate change, the guardians of the status quo variously deny reality, scapegoat the vulnerable, or go on vacation.

It is becoming ever clearer that systemic change is needed to avert total catastrophe, and people are fighting for it. Nuclear weapons may not have spread all over the world, but nine countries hold them, and in the hands of even the most prudent stateswoman, they are unacceptably dangerous. We must eliminate them.

Economic inequality, which poses enormous risks of civil unrest and breakdown, is a matter of policy.

The comic book supervillains who would subjugate the 99 percent to artificial intelligence can and must be held to democratic account, as must the industrial abusers of antibiotics.

The to-do list is extensive, but every single existential threat identified by the technocrats of the clock can be averted by popular action. Together, we must rise to meet the challenge.

There is one more charge against the clock, which, though rarely acknowledged, is of crucial importance. Conceived by American scientists at the heart of the Western nuclear complex, it focuses exclusively on the fate of a technologically interconnected, capitalist civilization.

Many other clocks have yet struck midnight all over the globe, as the cosmologies of countless indigenous societies have been disrupted – often irreparably – by ecological, industrial, or atomic damage. Some worlds have already ended. We must remember their struggles in the political fight for our own survival.