“There’s such a thing as having too much history,” a grad-school professor of mine once said, speaking of the troubles in Northern Ireland. Coming from a history professor, I found those words somewhat odd, and a bit condescending, but perhaps not entirely wrong.

Eventually, the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 and an open border with the Republic of Ireland made possible by European Union membership helped heal the wounds of the past, and provided a foundation for a more hopeful and forward-looking Northern Ireland.

But over two decades after the Good Friday Agreement, the peace and prosperity of Northern Ireland is in jeopardy again. This time, however, it’s not the sectarian traditions of Ulster that pose the immediate threat. In 2019, it’s a backward-looking version of English nationalism, which inspired the Brexit vote, that has cast a shadow over Northern Ireland.

Troubles and Good Friday Agreement

Progress toward peace in Northern Ireland has been real and inspiring, but it remains vulnerable. Significant compromises made by both unionist and nationalist leaders in 1998 led to the Good Friday Agreement, which created structures for power-sharing among the various opposing political parties of the region, helping to bring an end to three decades of violence known as the Troubles.

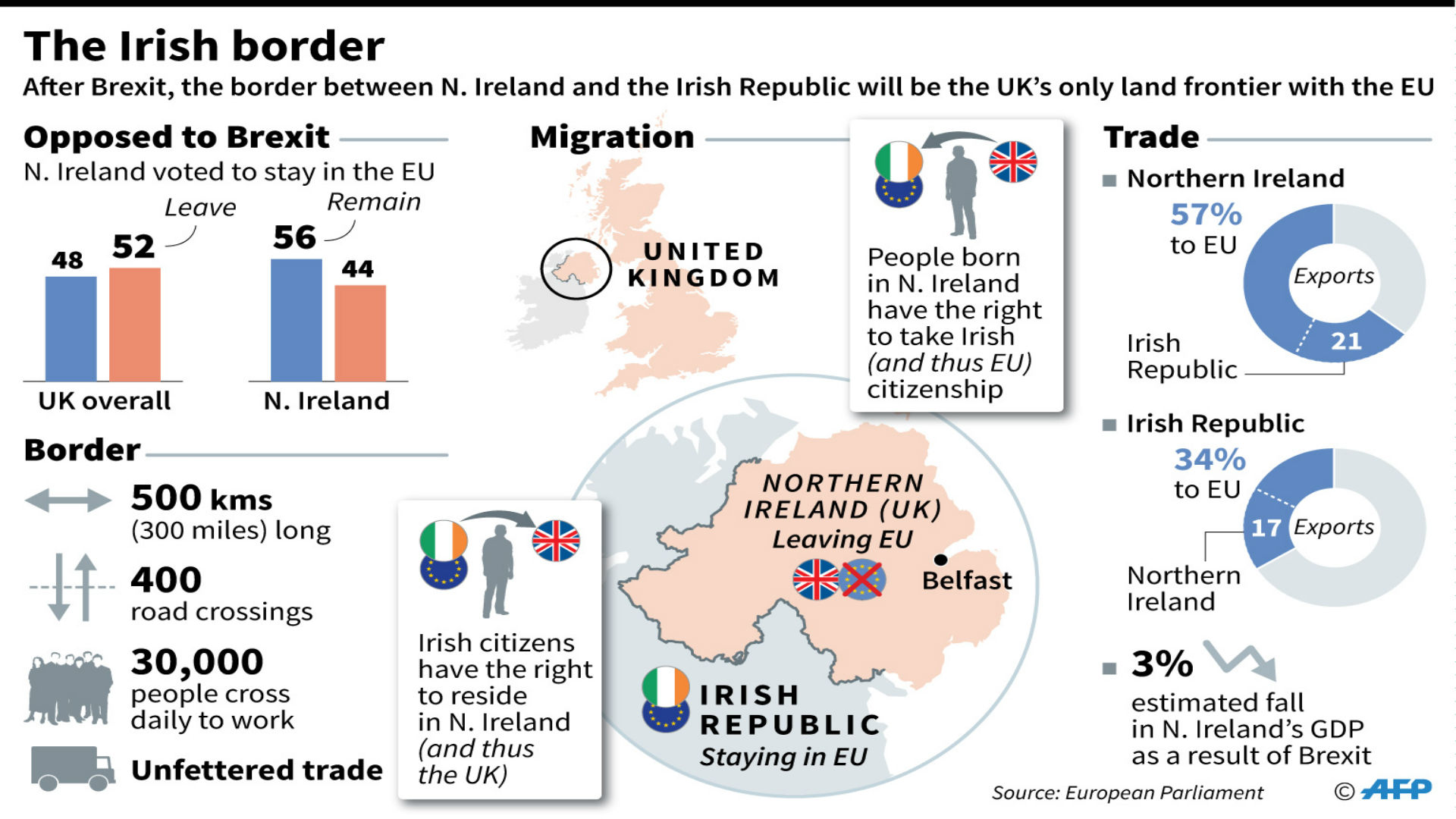

But building peace in Ireland has been an economic, as well as political, enterprise. Since the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom, of which Northern Ireland is a constituent part, are both members of the European Union, an open border between the two has helped foster important economic ties.

Economic relationships have been bolstered by the efforts of local citizen-led peacebuilding organizations on both sides of the formerly troubled border.

Brexit: Return of Sectarian Violence?

All of this is threatened by Brexit. If the United Kingdom leaves the European Union, as it is imminently scheduled to do, a formal or “hard” border could emerge once again. If it does, it could undermine more than twenty years of progress.

First, it would fracture the commercial ties between Northern Ireland and the Republic, likely hurting those who live closest to the border most, but undoubtedly causing economic hardship. Northern Ireland’s civil service chief, David Stirling, has warned that the sudden imposition of tariffs caused by a “no-deal” Brexit, the most dreaded but ever-more-likely option, would lead to “grave” consequences, including sharply increased unemployment and devastation in the agricultural sector.

But there is also a tremendous concern in both the north and south of the island that a hard border could lead to a second devastating effect of Brexit: a return of sectarian violence.

In theory, once the U.K. is no longer a member of the E.U., customs checkpoints would become necessary along Northern Ireland’s border with the Republic of Ireland. This would require border infrastructure that could become a target for dissident paramilitary groups who have refused to give up their arms. Attacks could lead once again to a militarization of the border, which could lead to further violence, causing the region to spiral back toward the Troubles.

Irish Backstop

Fears of such economic hardship and political violence have led to the British government’s attempts to negotiate an “Irish backstop,” a somewhat clunky term for a Brexit workaround in Ireland. If implemented, the backstop would leave the border as it is, and provide for free movement between Northern Ireland and the Republic to its south.

The problem, of course, is that like Prime Minister Theresa May’s Brexit deal in general, the backstop has created controversy, especially among the fiercest Brexit proponents, and so far, no Brexit deal has been reached.

As the situation now stands, in the likely event that May cannot pass a workable Brexit deal by March 29, a sudden and almost certainly chaotic “no deal” Brexit would go into effect, followed by the abrupt appearance of a hard border in Ireland.

To its credit, the government of the Republic of Ireland has made efforts to prepare for the disruptions that would be caused by a hard Brexit. The recently-passed Irish “Brexit Omnibus Bill” attempts to contain Brexit damage by addressing key issues like transportation, workers’ rights, healthcare, and energy.

Irony to Ireland’s Situation

Regardless of what happens between now and March 29, there’s a terrible irony to Ireland’s current situation. The progress of the last twenty years in Northern Ireland required nationalists and unionists alike to look forward and to reject the violent struggles that had marred the region’s history. The Good Friday Agreement, for example, required its signatories to let go of the past, at least to some degree.

The Brexit movement, on the other hand, was led by nostalgic nationalists like the race-baiting charlatan Nigel Farage, former leader of the extreme Euroskeptic United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), and the irresponsible and dishonest Conservative Party politician Boris Johnson.

The likes of Farage and Johnson railed against “bureaucrats in Brussels” and waged a mendacious campaign filled with images of past British greatness. They did not offer realistic proposals for Britain’s future, but outdated fantasies of imperial glory. UKIP’s pro-Brexit “Independence Day” ad opens with images of World War II-era spitfires and features black-and-white footage of a steam train and clips of Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1952.

Rather than fetishizing or desperately clinging to history, Brexiteers should try to learn from it. Like other nationalists, they tend to fear supranational institutions like the E.U., viewing them as a threat to freedom, independence, and prosperity. But the last 200 years have vividly illustrated the menace of nationalism itself, from the atrocities of the empire to the World Wars and the Holocaust.

This makes a recent surge of right-wing nationalism in Europe, which includes the Brexit movement, especially troubling. Supranational institutions, flawed though they may be, represent nothing like the peril of nationalism.

European Union

The European Union, does, of course, have its problems, and requires significant reforms.

It should be more transparent and responsive to the European people, it should be less beholden to neoliberal financial interests, and it needs to address the vexing contradictions caused by a common currency not connected to a common fiscal policy. But at its core exists a laudable vision, and one worth saving: a peaceful, prosperous Europe without borders or armed conflicts.

Northern Ireland has served as testimony to the positive potential of such a vision. Brexit offers nothing of the sort, relying instead on romantic, backward-looking nationalist fantasies, greatly overstating the U.K.’s place in the current global economy.

People in every region of the U.K. will almost certainly suffer as a result of Brexit, but the people of Northern Ireland may have the most to lose. It is not surprising that they voted remain by a 56-44 margin.

Sadly, after twenty years of trying to move forward, the people of Northern Ireland may just find that the effects of Brexit bring back a painful past.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.