As a historian working on 19th-century US history projects over the past couple of years, I have read numerous scholarly books and articles on the last two decades of the Antebellum and subsequent Civil War. It soon dawned on me that at night I was watching news that mirrored what I was reading in the morning and afternoon.

Astonished by the historical parallels between the Antebellum and contemporary developments, I began writing a series of comparative essays. This is part 2. Read part 1 here.

In July, CDC director Robert Redfield blamed northerners who headed south for Memorial Day weekend vacations for the latest surge of COVID-19. Harvard scientists and New York Governor Mario Cuomo retorted that it was not the North’s fault, blaming instead the increase on southern politicians who decided to reopen their states too soon.

Likewise, states are divided on mandates about wearing or not wearing masks, roughly along the Mason-Dixon line, the same two sections which during the Antebellum and Civil War were bitterly and violently split over slavery, its expansion, and a few other interrelated socio-political matters.

Historical Precedents

Founding Father and fourth US President James Madison, with his extraordinary political wisdom and foresight, could not have anticipated that so many Americans would come to cherish the freedom to not wear a mask as almost worthy of inclusion in the hallowed Bill of Rights. No one would have conceived just three months ago, that such an issue would divide the nation to the extent that it has.

There is somewhat of a historical precedent, however. During the Spanish Flu pandemic (1918-1919), opponents of mask-wearing ordinances organized and marched in protest in many US cities.

Anyone barely familiar with the Reconstruction Era that followed the Civil War and its long conflictive aftermath knows that the peace signed at Appomattox, far from healing the wounds of division, aggravated sectional and interracial tensions. It also gave way to long decades of systematic exploitation of former slaves, their illegal disenfranchisement, segregation, and lynching.

Sectionalism in North America actually precedes the formation of the United States. It reflects the reality of a vast territory divided by latitude and climate, thus by different economic activities, and hence by divergent economic interests, labor systems, domestic policy objectives, and even foreign policy.

The Antebellum South was geographically suited for producing tropical and semitropical staples such as tobacco, rice, cotton, and sugar, which many landowners believed required enslaved labor. While the North imported part of that production, much of it headed toward European markets, resulting in southern politicians’ insistence on friendly relations with Europe and keeping tariffs as low as possible.

Contrastingly, since colonial times, the northern economy focused on temperate climate agricultural activities, commerce, navigation, and manufacturing, a system that thrived on high, protectionist tariffs and did not depend on slave labor.

Historians have long recognized southern secessionism as a form of nationalism, whereby many white southerners viewed themselves as constituting a different nation with its own distinct culture, and therefore deserving of political autonomy, if not independence.

The North had its own form of nationalism, which strove to preserve the Union at whatever cost necessary. The Civil War was the culmination of tensions between southern secessionist nationalism and northern unionist nationalism.

A belt of five border states, meanwhile, extended west from Delaware through Missouri. Neither slavery nor southern nationalism were particularly strong in that region, and none of those states seceded.

Before the secession of 11 southern slave states, the formation of the Confederate States of America, and four years of all-out civil war, the North-South divide had been intensifying for decades.

It reached an explosive climax in the 1860 presidential elections, when party alignments overlapped sectional divisions to such extent that northern Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln carried all free states (northern [except New Jersey] and western) and lost all southern slave states. He did not receive a single popular vote in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North and South Carolina, or Texas.

From the Blue and the Grey to the Red and the Blue

Since the 1990s, but particularly following Barack Obama’s 2008 electoral victory, sectionalism, rural versus urban antagonism, and other manifestations of geographical political rivalry have remerged with a vengeance. This was exacerbated during the first years of Donald Trump’s presidency and reached feverish levels of vitriol and violence in 2019 and 2020.

As was the case during the Antebellum, Civil War, and Reconstruction, these conflicts are intertwined with manifestations of nationalism, partisan politics, and secessionist sentiments.

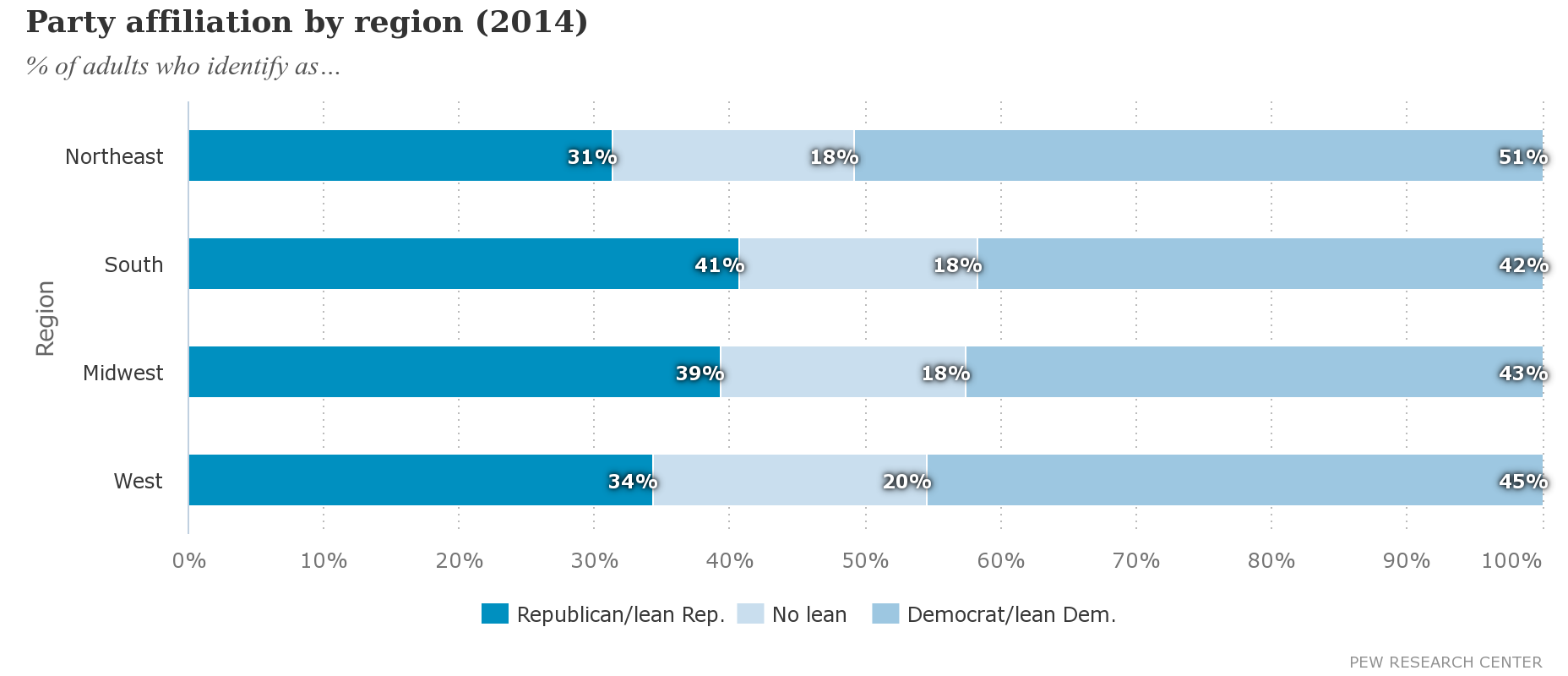

While the correspondence between political party affiliation and geographical region is nowhere close to what it was 160 years ago, geography still matters. According to Pew Research Center polls, in 2014, there was a clear overlap between region and party affiliation with 51 percent of North-eastern voters identifying as Democratic/leaning (only 31 percent Republican/leaning). Republican affiliation was much stronger in the South at 41 percent, a statistical tie with Democrats (42 percent).

An examination of the 2016 presidential electoral map reflects uncanny parallels with its 1860 counterpart. Map colors are, of course, inverted because the Republican and Democratic parties have since swapped ideological positions regarding many issues, including civil rights, race relations, and social justice. What has remained constant is the social conservatism and states’ rights ideology of the South.

Out of the 29 states that voted Republican or Democratic in 1860, all but seven went to the opposing party in 2016. Among them were Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, where Republican candidate Trump won by margins of less than 1 percent and a combined total of 78,000 votes.

Tellingly, the political party inversion rate between 1860 and 2016 was 100 percent in New England, the Southern, and Pacific coast states.

Urban-Rural Political Divide

During the Antebellum, cities overall leaned more Republican than Democratic, and rural areas are still more conservative than urban centers. These political correlations overlap with contrasting demographic and cultural realities: racially diverse and multicultural cities and apple-pie and Chevrolet truck rural settings.

Stanford University Political Science Professor Jonathan Rodden, who studies the growing political divide between urban and rural areas, has gone as far as stating that contemporary political polarization “is all about geography.”

Don't believe me? Just look at any election map. pic.twitter.com/RBGNiF7pjP

— Noah Smith

(@Noahpinion) September 16, 2019

A 2018 Pew Research Center poll assessing political and ideological differences among urban, rural, and suburban adults found wide gaps and polarization between urban and rural residents in views about Trump, immigration, abortion, and same-sex marriage.

Interestingly, the researchers concluded that such differences had more to do with party affiliation than with geographic setting. Urban Republicans are significantly more moderate (more evenly split) than their rural counterparts.

The urban-rural political divide has been growing for a couple of decades. In 2008, defeated red presidential candidate John McCain carried 53 percent of the rural vote. Eight years later, Trump received nearly twice as many rural votes (62 percent) as blue candidate Hillary Clinton, who got just 24 percent.

Suburban America, meanwhile, has become purple, mirroring the Antebellum’s frontier states. May the metaphor of battleground states and regions remain so.

Three Neos: Nationalists, Confederates, and Secessionists

Just like Lincoln was unacceptable to the white South in 1860, Obama’s election was intolerable to broad segments of the electorate in 2008. His election gave rise to numerous radical conservative groups and movements, starting with the Tea Party formation in February 2009.

Likewise, the United States has seen an upsurge of neo-confederate militancy and racial hatred and violence, far beyond the geographical limits of the old Confederacy. Confederate flags are flying in states like Mississippi and Alabama but also in old unionist states like Michigan and Wisconsin.

As fringe as they may be, neo-secessionist organizations and petitions multiplied after Obama’s election. They have quieted down in the last few years but are likely to mobilize if Trump does not win re-election.

War of the Masks

A recent Pew Research Center poll on mask-wearing practices shows some fascinating, if not completely surprising, correlations.

Northeasterners responded that they “always” (54 percent) and “very often” (23 percent) wore masks outside their homes. Numbers are much lower in other regions; the Midwest, for example, reflected that only 33 percent of its adult population wore masks all the time and another 29 percent very often.

There was an even stronger correlation with party affiliation with 94 percent of reds wearing masks either all the time or very often, compared to only half as many blues (46 percent). Only 1 percent of Democrats never wore masks, in contrast to 27 percent of Republicans.

It appears that to wear-or-not-wear a mask is today’s single most politicized and polarizing issue.

There have been dozens of instances of verbal and physical violence, even deaths over mask-wearing. Are Walmarts, Dollar Stores, and Waffle Houses the counterparts of Bleeding Kansas and Harpers Ferry, the rehearsals of the US Civil War?

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.