The gilets jaunes (yellow vest) movement started in mid-November and is a “recognizable” French socio-political phenomenon, using a classic French tactic: blocking roads so that the government will listen to their grievances, just like farmers, truckers, and others had before.

A notable distinction this time was the movement’s ambition to block the transport system across the whole country. The government’s approach was to wait and see, a tactic that had proved successful in the past. Since Emmanuel Macron’s election in May 2017, all the predictable protests led by the trade unions, public sector workers, or the far-left La France Insoumise (France Unbowed), had been failures, leaving the president untouched to continue his reform program.

Bizarrely, the yellow vest movement didn’t subside. It grew and grew and added demonstrations in cities to its repertoire, particularly in Paris, where violence erupted to the point that the government – for some even the “regime” – seemed in full retreat. Macron’s administration belatedly responded with a series of proposals, each of which dragged towards further conflagration and protest rather than calmed the situation.

How is it that this sudden organization without political experience, headquarters, leaders, and increasingly no specific demands, has provoked a month-long political crisis comparable to the events of 1968? What on earth happened? How are we to explain this hurricane?

Three factors, some classic elements, some new – and their novel combination – can help us grasp what is happening.

Tradition of Protests

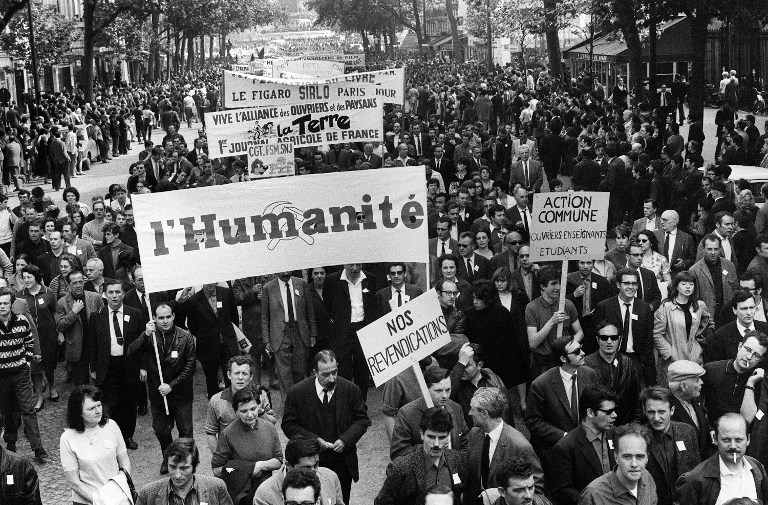

France is familiar with this kind of protests: truckers, farmers, and wider social movements have all protested before, for example, the bonnets rouges in 2012, the manif pour tous in 2013, and others in 2006, 1995, 1986, and of course 1968.

The phenomenon exists because of a range of factors. Firstly, France has a highly centralized state that rarely enjoys consensus. Secondly, there are deep and diverse intellectual traditions, particularly on the far left and right. Lastly, the country has a revolutionary heritage born in 1789 that still lingers.

The British political activist Emmeline Pankhurst said of the British government that nothing was ever won without something approaching a revolution. This is a hundred times truer for France. Uprisings like the yellow vest movement have violence on tap, even though the protestors themselves are overwhelmingly non-violent.

France has a highly active casseur tradition (casser means to break): small, armed revolutionary groups of the far-left and right (as regards the yellow vests mainly far-right) who, along with looters, latch on to the peaceful demonstrations and cause mayhem through confrontation with the police, destroying property, setting up barricades, and starting fires. These groups are highly versed in the guerrilla tactics of “revolutionary” situations and apply classic revolutionary theory: provoke the state to the point where it retaliates and instigates a wider conflagration – the conditions for a “real” revolution.

Even from a reformist perspective, it had to be admitted that the violence of the last month, particularly in the Champs Elysées on Saturday, December 1, was a major factor in getting the government to respond to the deteriorating situation.

Two Frances

The second factor explaining the virulence and political seriousness of the yellow vest movement is that it reflects an uncomfortable truth, namely that there are, and have been for a long time, “two Frances” (at least) instead of “one and indivisible republic” that the national narrative would have us believe.

There is the established, employed, and secure France on one side, and the unemployed, precariously employed, and generally disaffected on the other. In many ways, poor France is suffering because better off France cannot actually afford, for example, the health service it enjoys.

Not surprisingly, the yellow vests belong to the poor France. It is difficult to be one hundred percent accurate as to who they are because they have no organization, but generally speaking, they are low paid, owners of small businesses going under, ambulance drivers, night workers, plumbers, hospital porters, cleaners, and so on. Many of them have two jobs, both insecure, to try to make ends meet.

The yellow vest sentiment (and sympathy) also comes from an idea of fairness deeply embedded in the French psyche. France is, however, a country of major income disparities. For many French people, this is unjust, particularly in a world where companies like Google, Amazon, and Apple make enormous profits yet pay virtually no taxes. Macron was going to change that world to one that was efficient but also fairer.

It is ironic that one of the reasons Macron came to power (like the yellow vests, from nowhere) was because he, like many of the French, wanted a “new France:” a non-party political and citizens’ France where ideas come from the people. Where Amazon pays its fair share. Where the disparity between rich and poor is not obscene. Where everyone is productive and happy. A radical centrism where the mass of reasonable people speaks their mind. With the yellow vest movement, that is exactly what Macron got.

Change was expected following his election. Macron would bring a new system, but unemployment and job insecurity remained stubbornly the same. This could only be one person’s fault, which brings us to the third element to an understanding of the yellow vest protests: the personalization of power in France.

Personalization of Politics

France’s personalization of politics is not only institutionally (and in this is more akin to Russia than the United States), but also symbolically.

The huge irony here is that the yellow vests are leaderless. They can’t even find a spokesperson let alone a coordinating committee or leader. They are a pure product of social media. The character of their movement is spontaneous, anti-system, and anarchic in its true sense.

The politics of France, on the other hand, are highly personal. And Macron knew this. As a presidential candidate, he tapped into a generalized social and political frustration present in French society against the establishment.

Once elected, however, Marcon reverted to a lofty Gaullism – conservatism, nationalism, and advocacy of centralized government – not seen since Francois Mitterrand in the 1980s. The power-lines remained vertical and centralized. Even his new political party, La République en Marche, was more like an echo chamber than the anticipated new citizens’ party. This was partly the result of Macron himself knowing he had to move fast with his reforms; but because of the expectations his new kind of politics raised he should have moved even faster and more fairly.

It is true that the French themselves yearn for the protection of an all-powerful president-king, at the same time as wanting to be heard. Macron grasped the first part of this paradox (having in recent memory the garrulous ineffective leadership of his predecessor Francois Hollande), but forgot the second, protecting the people.

In his first year in office, Macron’s image reflected the poor advice he was getting from his equally young inner circle of advisors. The result was that instead of coming across as the good young king, he became the pushy, demanding, careless director of a new start-up called France.

Abrasive and impatient, he treated the French (often when speaking publicly abroad as if mocking his own people) as lazy, ungovernable, hostile to reform, and needing to be prodded into the modern world. On top of this infelicitous comments, there were a few personal scandals that every highly personalized institution is vulnerable to: essentially, of the not practicing what he preached kind.

With a regime as personalized and politicized as that of France and austerity measures plus rising taxes that make the cost of living unbearable for many, the conditions for a perfect storm were gathered.

Macron’s Speech

At the center of this gathered perfect storm was Macron’s long-awaited, 12-minute speech on Monday.

As a piece of theatre, performance, and rhetoric it was a masterpiece: a wounded and contrite but dignified president accepting his mistakes and acknowledging the legitimacy of the grievances, promising a range of immediate financial and longer-term democratic reforms. This was unthinkable only three weeks before and make the yellow vests arguably one of the most successful protest movements of modern times.

Obstacles for Reaching Solution

Two factors, however, both of which militated in the yellow vests’ favor, now militate against a resolution of the problem.

First, without an organization, structure, leadership, set of aims, and direction, this movement which has transformed itself from a protest about petrol prices to demands for a new way of life, does not know where to go and how to respond to Macron’s outstretched hand.

Second, everything is focused, as it was on Monday night, upon the persona of the president. For many in the movement, he is the legitimate target. Their aim is to make him resign, but that would only take France into political and social chaos of a much larger scale than that of the yellow vest movement.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.