By March 12, and perhaps this week, the U.K. Parliament will vote again on the Withdrawal Agreement with the European Union. In January, the previous deal was rejected in the largest legislative defeat ever suffered by a British prime minister.

If defeated again, Prime Minister Theresa May has already accepted, against her will, that the parliament will be able to legislate to prevent the U.K. leaving “without a deal,” and to allow an extension of the negotiations beyond the scheduled exit on March 29.

#Brexit – No deal is not an option for us. "I hate the no deal scenario. I want a fair deal" @JunckerEU #EUCO pic.twitter.com/muaWdyZmRr

— European Commission (@EU_Commission) October 20, 2017

That, however, would require the approval of the European Council, consisting of all heads of state and government of E.U. member states.

Unless the U.K. is headed for a snap general election to resolve its parliament’s inability to make key decisions, or unless it heads for a second referendum – in which citizens would presumably vote to accept May’s deal or to stay in the E.U. – it is not yet clear why the E.U. should oblige the request, and, if so, for how long.

What can May do to succeed in getting her deal through parliament, while avoiding further dependence on the European Council? Her strategy, more or less out in the open, has three components: blackmail, bribery, and betrayal.

Blackmail

May has achieved the blackmail component by running down the negotiating clock, confronting her party’s hardliners with what some call the choice between “suicide” and “vassalage.”

The first choice, suicide, represents a hard exit without a deal for which the U.K. is palpably ill-prepared. The vassalage option means accepting May’s deal, which would ensure the U.K. leaves the E.U.’s institutions, but in key respects produces a U.K. exit in name only (UKEXITINO).

It would be a UKEXITINO because during a potentially long and extendable transition, the U.K. will be subject to E.U. laws, and because of the terms of the Ireland–Northern Ireland Protocol attached to the Withdrawal Agreement.

Bribery

The bribery is primarily targeted at Labour MPs who represent places that voted heavily to leave the E.U. in the 2016 referendum. Spending proposals are being advanced that deliberately target these constituencies, and late in the day, May has promised that workers’ rights will be protected after exit.

If the blackmailed bend and the to-be-bribed stay bribed, May can hope to increase the numbers backing her deal. But to succeed, the prime minister thinks she also needs to engineer a betrayal.

Betrayal

That betrayal, also in the public domain but currently being negotiated in private, seeks to modify the “Irish backstop,” the popular name given to the legal protocol agreed between the U.K. and the E.U. 27 (including Ireland) in November as part of the draft agreement.

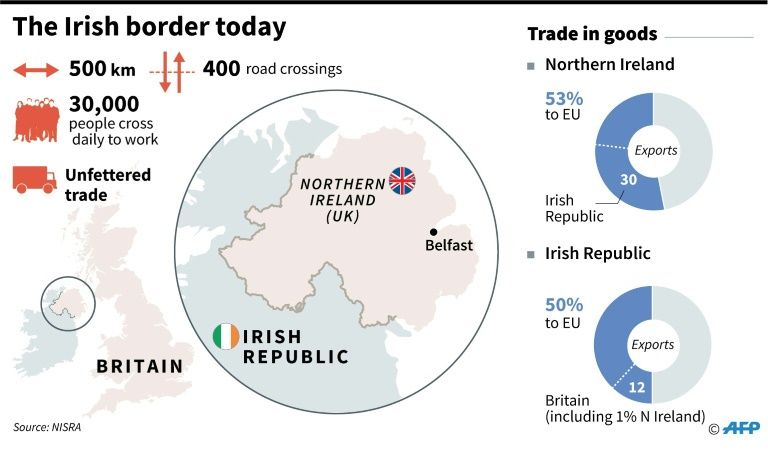

The backstop firstly ensures that the U.K.’s exit will not recreate a hard border (for customs or regulations) on the island of Ireland or in the Irish Sea unless “alternative arrangements” to avoid such can be agreed.

However, British politicians tend to forget the second and third component of the backstop. It also preserves North-South border co-operation across the island and protects both citizens’ and non-citizens’ rights currently protected by the separate and sometimes overlapping functioning of the Good Friday Agreement, the European Union, and the European Court of Human Rights.

The Protocol emphatically specifies that its provisions will continue in force “unless and until they are superseded, in whole or in part, by a subsequent agreement.” That’s what drives the self-styled Brexiteers berserk: the Protocol “in international law … would endure indefinitely until a superseding agreement took its place, in whole or in part,” the exact words of the U.K.’s Attorney General Geoffrey Cox.

In short, the Protocol expresses an E.U.27 veto, effectively in Ireland’s hands.

Irish Border

The problem for May is that if her deal is ratified, no one can credibly believe that there could rapidly be a replacement deal – on trade and other matters – to supersede the Protocol. May has, therefore, shamelessly, promised her party colleagues that she will endeavor to negotiate changes to the backstop so that the U.K. is not trapped forever.

Differently put, she seeks to betray the commitment she has made several times, to protect the Good Friday Agreement in “all its parts,” the open border on Ireland, and the rights provisions, most recently in this very Protocol.

But can such a deed be accomplished in broad daylight?

The backstop would have to come into effect after the withdrawal agreement is ratified because the E.U.-27 and the U.K. will not be able to reach a superseding agreement with any rapidity. Moreover, the more the E.U. seeks to appease May, the more it risks losing its successfully accomplished solidarity and support for Ireland during these negotiations.

What might the betrayal be? May will have to imply that the backstop is somehow more temporary than it is understood to be – it is temporary; it is just that the exit from it is subject to a mutual veto and arbitration. The words will have to suggest that the U.K. has a unilateral exit capacity.

Whatever lies may be told to finalize the withdrawal agreement with the European Union and extricate the U.K. from the Irish backstop, they will hardly be noble.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.